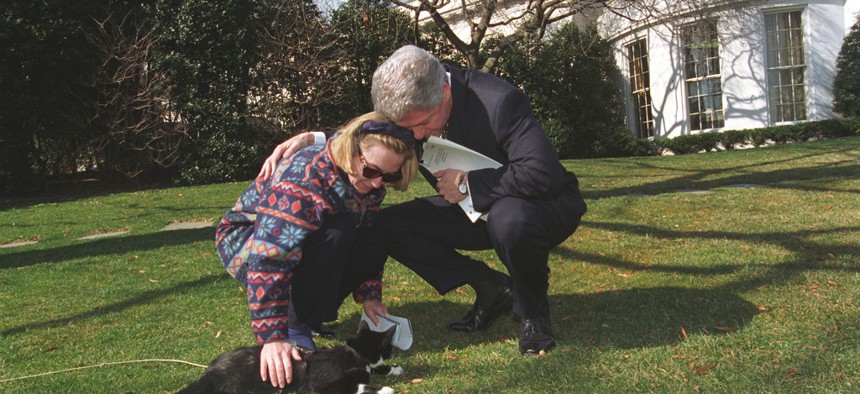

Hillary Clinton's name has been familiar since she was residing in the White House with her husband Bill and their cat Socks in the 1990s. National Archives

Is Hillary Clinton’s Famous Name Boosting Her in Early 2016 Polls?

Familiar names have tremendous psychological power.

Hillary Clinton is beating everyone. A recent CNN/ORC poll found that when Clinton is matched up against every probable 2016 opponent—Democrat and Republican—she wins.

"None of the top candidates in this field gets within 10 points of Hillary Clinton," CNN wrote. The poll was conducted March 13-15, (after news broke of her email controversy) and had a margin of error of plus or minus 3 percentage points. It adds to the narrative that 2016—or at least the Democratic primary—is Clinton's to lose.

Clinton won this hypothetical election, but she also wins another contest: name recognition. Ninety-nine percent of poll respondents said they were familiar with the former secretary of State.

What about her Republican competition? Forty-eight percent said they have never heard of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker. Fifty-six percent didn't know neurosurgeon Ben Carson, and 39 percent were unfamiliar with Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida. Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush was the most recognizable Republican, but 14 percent of poll participants had never heard of him.

What that means is this: For about half of Americans, the question "Who would you vote for: Hillary Clinton or Scott Walker?" is effectively "Who would you vote for: Hillary Clinton or some Republican governor?"

Many Republicans will choose "some Republican governor" over Clinton no matter what. But if national elections are swung by independent voters (who may or may not exist in practice, but that's another story) we can't really know if independent respondents in the CNN poll are picking Clinton because they like her, or because they're more familiar with her.

Research suggests that when voters don't know much about candidates in a given race, name recognition sways electoral choices. In 2013, researchers at Vanderbilt University tested this theory in an experiment involving subliminal messages and a fake election between two fictional men: Mike Williams and Ben Griffin.

Before the mock election, participants in the experiment saw letters and words flash by in rapid succession on a computer screen. In this flurry of words, half the participants saw the name "Griffin." But they didn't realize they saw it: The name flashed on screen for a total of 40 milliseconds. That's .04 seconds, barely enough time to record a thought. Psychologists call this priming, a process by which small, subtle cues can change future behavior.

Then, came the test, a simple question: "Imagine two candidates are running for political office: Mike Williams and Ben Griffin. If you were eligible to vote in this election, for which candidate would you vote?" Participants were not given any further information about the candidates, like party affiliation.

For those who had seen the name "Griffin" flash on screen for barely an instant, "Griffin" had a 5-point advantage at the ballot box. "Name recognition provides a sense of viability," says Cindy Kam, a coauthor of the study. "In cases where people have not heard of a challenger, then it's very difficult to imagine that challenger could be viable."

The computer scenario actually isn't all that contrived: consider the amount of time a person spends looking a campaign yard sign while breezing by in a car.

Kam says it's unlikely that name recognition is a factor in general elections. Come Election Day, both the Democratic and Republican candidates are household names. But it is possible, she says, that name recognition affects voter sentiment in early polls.

"These polls that are happening even a year before anything, this is a low-information context," Kam says. "This is where name recognition matters."

In the same poll, CNN also asked Republicans and Democrats about their respective primaries. It found that Bush is winning the GOP primary race, with 16 percent of Republican respondents saying they would vote for him. The runner-up is Walker, with 13 percent. The poll's margin of error is 4.5 percentage points. But if Bush is the front-runner in the poll, is it because he's truly more well-liked, or is it because more people know who he is? After all, 86 percent of respondents recognized Bush, versus the 52 percent who recognized Walker. The effects of name recognition may be stronger in party primary polls than in general-elections poll because respondents aren't choosing between parties, just names.

The same goes for Clinton when she's pitted against the lesser-known Democrats who may run against her. Vice President Joe Biden has a very recognizable name (just 6 percent said they didn't know him), but he's trailing far behind Clinton. That could be in part because voters don't see him as viable a candidate: just 15 percent of Democratic respondents chose him for the Democratic nomination. (To be fair, the vice president has made far fewer gestures to suggest he's running.) CNN didn't bother to ask respondents if they knew former Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley, who has been hinting at a White House bid. The poll has him at 1 percent in a hypothetical Democratic primary, but his numbers will likely rise should he announce he's running.

In the long run, however, the numbers from these early head-to-head polls don't mean much.

"The idea that at this point that these trial heats may reveal something about Election Day, I don't see any value there," says Jon Krosnick, director of the Political Psychology research group at Stanford University and an expert on survey research methods. "These politicians have not yet begun to campaign."

But when they do, will these early polls hurt or help their momentum? In other research, Kam has found evidence that early polls can influence future poll results. Trailing candidates are more easily discounted, while those in the front of the pack gain greater attention. "When people feel like a candidate has no chance, they are less likely to be curious about that candidate and less likely to search on Google for the candidate," she said.

Though early polls have little predictive value for voters, they might influence the elites who are deciding where to spend their money. Republican donors might see CNN's poll, for example, and conclude that Bush is a safe bet.

Low name recognition doesn't necessarily mean candidates like Walker and Carson are going to lose. Clinton's name comes with political baggage; theirs might not for a large percentage of voters. And the Republican contenders know that. "There is a great opportunity to be had in not having the same name recognition as the more well-known candidates," Carson said in a statement to National Journal. Our American Revival, the Super PAC supporting Walker, framed the former governor's situation similarly. "He looks forward to talking with even more Americans about [his] reform ideas in the coming weeks and months," the group said in a statement.

Relative unknowns have reason to be optimistic. In 2006, when CNN asked poll respondents about a Barack Obama, 37 percent said they didn't know who he was.

NEXT STORY: Photo ID Cards Won't Stop Food Stamp Fraud