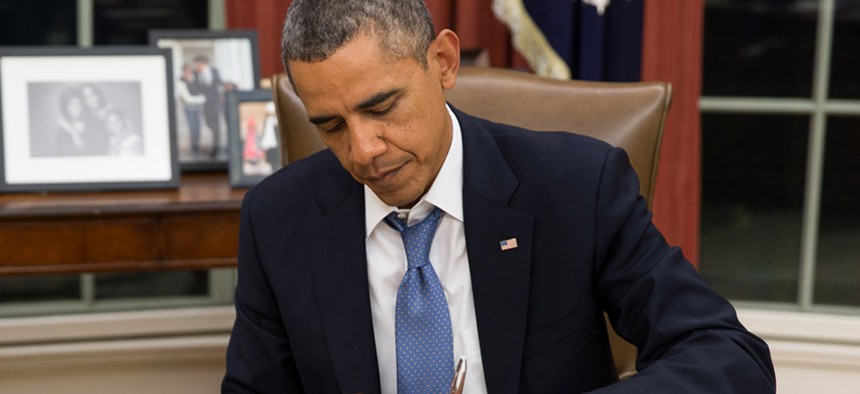

White House file photo

The Limits of Obama's Clemency

The president granted pardons and commutations to 20 on Wednesday, but many more wait.

Few presidential powers are as unconstrained as the pardon. Neither Congress nor the courts need be consulted, and neither branch can override its application. President Lincoln, the pardon's most prolific wielder, liberally exercised the power of mercy. "Gen. Joseph Hooker once sent an envelope to the president containing the cases of 55 convicted and doomed deserters," wrote one historian. "Lincoln merely wrote 'Pardoned' on the envelope and returned it to Hooker."

Barack Obama has been more restrictive. On Wednesday, the president granted clemency to 20 individuals—eight commutations and 12 pardons—for crimes ranging from counterfeiting in 1988 to "possession of an unregistered distilling apparatus" in 1964. This will change the recipients' lives, but thousands of applicants are not so lucky.

Presidential pardons have declined since World War II, excluding cases of mass amnesty like Jimmy Carter and the Vietnam draft-dodgers, but Obama's sparing use still stands out: Until Wednesday, one in seven of his pardons had beenissued for Thanksgiving turkeys. A 2012 investigation by ProPublica found that an applicant's chance of receiving a pardon under Obama was only one in 5,000, compared to one in 1,000 under George W. Bush and one in 100 under Ronald Reagan. Obama seldom grants pardons beyond the traditional holiday-season batch. His April 15 commutation of Ceasar Huerta Cantu's sentence is a rare exception. A typo had accidentally lengthened Cantu's sentence by 42 months, and a court ruled that only presidential clemency could correct the error.

But the handful of pardons issued Wednesday reveal something about American criminal justice. All eight commutations were for nonviolent drug-related offenses; four of the beneficiaries received life sentences simply for possession and/or conspiracy to distribute. "While all eight were properly held accountable for their criminal actions, their punishments did not fit their crimes, and sentencing laws and policies have since been updated to ensure more fairness for low-level offenders," Deputy Attorney General James Cole said in a statement.

These cases are not unusual. A 2013 ACLU report found 3,278 Americans serving life without parole for nonviolent crimes, more than 2,000 of them in the federal system. Their demographics are representative of those most affected by mass incarceration: Many struggle with mental illnesses and faced turbulent childhoods. Roughly 65 percent are black.

Even when pardons are made, they are susceptible to the same biases that plague the rest of the criminal-justice system. A 2o11 ProPublica investigationfound significant racial disparities in the process. Although the pardon office's clemency recommendations to the White House do not mention race, all but 13 of the 189 pardons issued under the George W. Bush administration went to white defendants, including all 34 of those who had committed drug-related offenses. Black inmates constitute 38 percent of the federal prison population but only received an estimated 2 to 4 percent of the pardons issued. In April, the Obama administration ousted U.S. pardon attorney Ronald Rodgers, a former military judge and federal drug-crimes prosecutor whose tenure was marked by blocked legitimate petitions and the withholding of key facts.

There are practical limits to pardons. Presidential clemency doesn't apply to state and local crimes, which account for the overwhelming majority of U.S. prisoners. Congress abolished federal parole in 1984, thereby limiting the president's ability to commute prison sentences. But Obama can still have a broad impact. As it removed Rodgers, for example, the Department of Justiceannounced a new clemency initiative that could free thousands of federal inmates held on drug offenses.

At least 2 million Americans currently sit behind bars, with twice as many more on parole, probation, or other forms of state supervision. A further 65 million Americans have criminal convictions that reduce their economic, social, and civic potential through collateral consequences. For a legacy-conscious president embracing unilateral action after losing control of Congress, pardons seem like a natural fit.