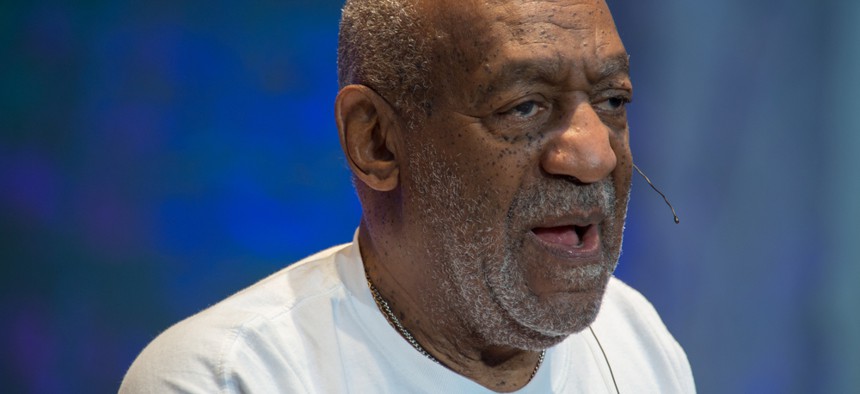

Randy Miramontez/Shutterstock.com

Why Is the Smithsonian Standing Behind Bill Cosby?

The comedian thinks people should have "the integrity not to ask" about the allegations against him. The institution apparently agrees.

Bill Cosby did not want to talk about rape with the Associated Press. That much he made clear in an interview with AP arts reporter Brett Zongker, who interviewed Cosby and his wife, Camille, upon the opening of an exhibit of their collection of African American art at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art. During the November 6 interview, which took place at the museum, Cosby rejected a question from the reporter about the allegations of sexual assault that have lingered over the popular performer—and national father figure—for nearly a decade.

“There’s no response,” Cosby tells Zongker during the filmed interview , which the AP released in its entirety on Wednesday. Seated in front of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s powerful 1894 painting, "The Thankful Poor," Cosby appeals to the reporter after the interview concludes (with the tape still rolling) to omit any discussion of the allegations of sexual assault. When that doesn’t appear to work, Cosby tells someone off camera, “I think you need to get on the phone with his person [Zongker’s employer], immediately.”

Now it’s the Smithsonian that doesn’t want to talk about rape. Through a spokesperson, both the National Museum of African Art and the larger Smithsonian Institution declined to discuss allegations from as many as 15 women that Cosby drugged and raped them. Two women, Joan Tarshis and model Janice Dickinson, have come forward with their accusations since the November 9 opening of “Conversations: African and African American Artworks in Dialogue.” A third woman, Therese Serignese, said yesterday that Cosby drugged and raped her when she was 19.

In a two-sentence statement, the Smithsonian made clear that it is standing behind Cosby, without saying as much. “Conversations” will remain on view through the start of 2016. That’s the end of the conversation from the museum’s perspective. But it should be the start of one. The National Museum of African Art had no business hanging Cosby’s art collection in the first place. But now, with serious questions about Cosby’s past finally coming to light, the Smithsonian must reconsider its own role in framing the one conversation that matters most right now.

“When you choose to launch a show about a collector, rather than a show about art, you’re putting the collector on the pedestal, rather than artists and art and its history,” says art critic Tyler Green, host of the popular Modern Art Notes podcast and blog . Green, an art-world watchdog, has been a vociferous critic of exhibitions like “Conversations,” collector-driven shows in which the focus is the pursuit of artworks, rather than an artist or a theme. “That can go south really fast, and here, it has.”

The individual collector hardly matters, Green says. Collector-driven shows run contrary to the mission of art museums, which serve to tell the history of art and its makers. While there does exist a school of thought that art history in fact is the history of its benefactors—a theory from the 1980s called the New Art History—critics today tend to dismiss this approach. And in practice, shows about collectors tend inevitably toward hagiography.

“Art museums, through their exhibitions or collection galleries, tell a story of accumulation: how artists accumulate knowledge from their cultures or the art around them,” Green says. “Turning the focus to acquisitors rather than artists makes the focus on accumulation a story about shopping.”

The Smithsonian has a record of condescending to viewers with thin collector exhibitions. “Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg,” a 2010 show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, traded on two of Hollywood’s biggest names for a scholarship-free presentation of one of America’s most overexposed artists. It was a blockbuster. The same museum planned an exhibit of Western ephemera from the collection of Tea Party backer Bill Koch, including Western art—like the celebrated nocturne paintings of Frederic Remington—but also non-artworks, like pickaxes and gold nuggets. (The show never panned out.)

Beyond their low nutritional value, there are other reasons to object to collector-driven shows. Collectors stand to see the value of their works rise after a museum exhibition, which is why museums should never entertain collector exhibits unless the collection is promised to the museum, as former Washington Post art critic Blake Gopnik explained by email. But that’s not the real problem with the Cosby show at the Smithsonian, he argues (putting aside, for a moment, the horrific allegations surrounding Cosby).

“How many collectors, buying only over a span of a few decades, have really amassed just the works an exhibition needs to make some significant art-historical point?” Gopnik writes. “In judging any curatorial exercise, I always ask, ‘What mark would this get if a student handed it in as an exhibition proposal in a curatorial studies class?’ A one-collector exhibition (even including some comparative objects from the permanent collection)? That would get a definite D-.”

The timing of this exhibition can't be seen as a coincidence. Cosby has been on a publicity blitz this fall. Bill Cosby 77 , an hour-long comedy special, was set to air on Netflix on November 27. (Netflix has since postponed the program, perhaps indefinitely.) A biography, Cosby: His Life and Times , was published in September to mark the 30th anniversary of The Cosby Show . (The book is now taking a drubbing .) Most notably, Cosby was set to reunite with Tom Werner, the producer of The Cosby Show , for a new NBC series. (That series has been cancelled.)

Even TV Land has pulled re-runs of The Cosby Show from its lineup. Only the Smithsonian is providing Cosby any cover. While it’s troubling to think that the National Museum of African Art can be lined up like an appearance on David Letterman—which, incidentally, Cosby cancelled—perhaps removing an art show in the face of controversy merits some debate. After all, it’s hardly the fault of the artworks that their owner is discredited. Removing powerful works by wonderful African American artists like Romare Bearden and Faith Ringgold does a disservice to museumgoers who want to see them.

The Smithsonian has censored an exhibit once in the recent past. In late 2010, Secretary G. Wayne Clough removed an artwork from an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. A 1987 video called "A Fire in My Belly" by artist David Wojnarowicz, one of the works included in “Hide/Seek” —a groundbreaking exhibition of portraiture by LGBT artists—drew the ire of a conservative activist-journalist employed through Brent Bozell’s Media Research Center. Just as Bozell’s Parents Television Council used to overwhelm the FCC with complaints about indecency on television, the Media Research Center flooded the National Portrait Gallery with hundreds of phone calls and emails, all registering the same ultra-specific complaint: "A Fire in My Belly" was anti-Christmas. (The surreal video artwork featured snippets of ants crawling over a crucifix.)

When then-ascendant GOP leaders John Boehner and Eric Cantor spoke in favor of taking down the queer-art exhibition, Secretary Clough took action: Over the objections of the museum’s then-director Martin Sullivan, Clough had the video removed. It was absolutely the wrong decision, and Clough later earned a (mild) rebuke from an outside panel organized by the Smithsonian’s board of regents. Artworks shouldn’t be removed from exhibitions that have already opened, the panel recommended . (Secretary Clough is retiring at the end of the year.)

In “Conversations,” the artworks are not the issue. (They present a skewed narrative of African American art history, writes Washington Post art critic Philip Kennicott in his review , but never mind.) It’s the show itself that is the problem. It should never have opened. Its origination calls into question the Smithsonian’s ethical standing as a fiercely independent public institution, and not a vehicle for celebrity. Removing “Conversations” would do the museum no harm.

“We’re not talking about a museum of art in Dubuque. We’re talking about the National Museum of African Art, which has a fine collection, and one of the finest collections of its kind in the United States,” Green says. “If it has to take down a show because it’s embarrassing itself, it’s not like they’ll be showing empty walls.”

Supporting “Conversations,” on the hand, invariably means supporting Cosby. But there might be a step short of pulling the exhibition: The Smithsonian could offer to strike the Cosbys’ name from the show. Pull down the Simmie Knox portrait of the couple that makes them look like modern-day Medicis. Scrub the word “Cosby” from the walls. That would show that the leaders of America’s cultural treasury are not willing to, as my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it , “take one person's word over 15 others.” It would no doubt lead to the show collapsing.

That would be for the best. In the AP video interview with Cosby, the gallery goes to a dark place. What happens in the room is an abuse of the dignity of an art museum. It’s not just Cosby telling Zongker to shut down the conversation, but several people. It’s not just the reporter that this room wants silenced, but by extension the women who have testified about their pain. One man from Cosby’s retinue tells Zongker that another AP reporter accepted Cosby’s refusal to discuss the allegations against him—and so should he. A woman off-screen whom Cosby doesn’t appear to know (he refers to her as “ma’am”) confirms Cosby’s opinion about Zongker’s line of questioning: “I don’t think it has any value, either.”

“We thought, by the way, because it was AP, that it wouldn’t be necessary to go over that question with you,” Cosby tells Zongker. (The original November 10 story mentions the allegations in the final paragraph of a 1,000-word piece on Cosby’s collection.) “We thought AP had the integrity to not ask,” Cosby adds.

Now it’s the museum’s turn to prove its mettle. Does the Smithsonian have the integrity not to ask? Or does it have the integrity the situation deserves?

(Top image via Randy Miramontez / Shutterstock.com )