White House Protestors Underwhelmed by Obama's Ferguson Comments

On a night of high national tensions and violence, protestors at the White House were disappointed by President Obama's speech about the Ferguson grand jury.

In a ceremony that fell between the bookends of an exceptionally turbulent day, President Obama posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom toJames Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner on Monday. The highest civilian honor for three civil rights activists, who were murdered by klansmen and buried in a dam in Mississippi while working to enfranchise black voters in the summer of 1964.

“James, Andrew, and Michael could not have known the impact they would have on the civil rights movement or on future generations," the president said. "And here today, inspired by their sacrifice, we continue to fight for the ideals of equality and justice for which they gave their lives.”

The event was too easy to miss. After all, it happened on a day that had started with the resignation of Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel and ended with the grand jury decision not to indict Ferguson Officer Darren Wilson in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown. Shortly past 10 p.m., after the latter announcement had been made, the president approached the podium at the White House to deliver a short speech .

Despite the national fatigue implicit with presidential speeches given in the sixth year in office (and beyond), Monday night was the occasion for which this president was seemingly delivered. And though he had been burned in no small way by previous speeches about the death of Trayvon Martin and the arrest of Harvard professor Henry Gates, one could be forgiven for wanting to catch just a glimmer of the orator who had once electrified many with his words on race in America.

Also, now doubly shellacked, there was perhaps a perverse hope that a man with nothing to lose might finally arrive at the pulpit. "Obama, you are a second term president. Say something real," he was implored . Here's what followed instead:

We need to accept that this decision was the grand jury's to make. There are Americans who agree with it and there are Americans who are deeply disappointed, even angry. It’s an understandable reaction.

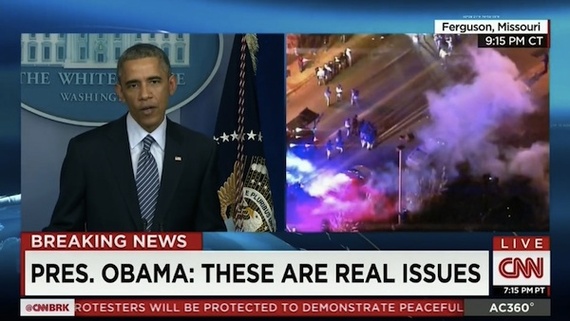

In a surreal twist, the president's flat appeal for calm was overtaken by the network split screens, which juxtaposed the sober presidential dais with the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, in a fog of smoke, an orgy of police lights, and chaos everywhere. America was rioting in the president's backswing.

Following the speech, as demonstrations and riots were taking place across the country, some 300-plus protestors, mainly college students from nearby Howard, George Washington, and Georgetown, had amassed down at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Outside the White House, the crowd alternated chants of " Hands up, don't shoot! " and "Black lives matter." At one point, several dozen demonstrators fell to the ground while shouting the names Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown.

Their feelings about the grand jury decision were evident, but since so many people had descended upon the plaza outside the White House, I asked a few of the demonstrators about the president's speech. With some disappointment, James, a sophomore at Howard, called it a "middle ground speech."

It was a regular speech. Calming, regular, not one way or the other. Like a president has to be. He showed support to Michael Brown's family and then told protestors to not be violent.

Greg, a sophomore at George Washington, defended the reasoning behind the president's comments. "It was of the most importance to just call for calm in the immediate aftermath of the decision," he told me. "But I'm sure in the coming days or even weeks, the president will have some deeper things to say. But right now, all he's concerned about is to make sure things are calm."

Taryn, a senior at Howard University, said that she wished the president could have delivered a speech that was "a little more real," but chalked it up to a reality that meaningful presidential speechifying about controversial issues is something of a false promise.

That struggle for meaningful symbolism doesn't go away. Rita Schwerner Bender, the wife of slain civil rights hero Michael Schwerner, was at odds with the White House's decision to deliver an honor to her late husband, saying that it "distorts history" to consign the ongoing civil rights movement to the past.

"There were not just three men who were part of a struggle. There were not just three men who were killed," she told the AP. "You know, the struggle in this country probably started with the first revolt on a slave ship, and it continues now."

NEXT STORY: A Public-Private Innovation Classroom