Will Congress Save the U.S. Postal Service?

A behind-the-scenes look at lawmakers’ inability to move forward on a desperately-needed overhaul.

Just about everyone agrees the U.S. Postal Service must change the way it does business.

It’s not hard to see why: In 1970, Congress overhauled what was then known as the Post Office to create USPS, allowing it to operate independently from the rest of the federal government and requiring it to break even financially each year. However, the Postal Service has recorded a loss in 21 of the last 23 quarters.

Ten years ago the agency annually delivered 60 billion pieces of first-class mail -- USPS’ most profitable offering, consisting of normal letters and bill payments -- while today it delivers about one-third of that total. Postal management estimates that yearly figure will continue to slide until it bottoms out around 5 billion or 6 billion pieces. Formerly the nation’s largest employer, the Postal Service has cut nearly 300,000 jobs since its peak in the late 1980s.

USPS still delivers to 153 million addresses in every town in America and is the backbone of a $1.3 trillion mailing industry, representing 8.6 percent of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product. Through rain, sleet, snow or dire financial instability, every single American can still expect a visit from a mail carrier six days each week.

Postal management, Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill, labor unions, the mailing industry and the Obama administration all agree on the need for congressional reforms to keep the agency – which still brought in $66 billion in revenue last year -- afloat. But there is very little agreement among those groups about what those reforms should look like.

In a series of recent interviews conducted by Government Executive , lawmakers and stakeholders wove a diverse and fragmented tapestry of priorities and solutions to fix the cash-strapped Postal Service, with the only common threads found in the need for change at all.

“I think the major problem with postal reform is that as an industry, we’ve never really coalesced,” says Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe. He adds each sector of the massive mailing industry -- from competitors like UPS and FedEx to the myriad businesses that depend on mail delivery -- identifies a different element as the one key issue on which they cannot give in.

Since 2006, the last year in which Congress approved postal legislation of any significance, many have tried to usher a postal overhaul into law, but none have succeeded. And while lawmakers consistently claim they were and are this close to having votes for a comprehensive piece of legislation, partisan divides, lobbying efforts by labor and industry groups, and an array of competing interests have made postal reform one of the most sought-after-yet-elusive issues before Congress.

2006: Minimal Controversy

To understand where postal reform is heading, one must first look at the path it has taken to get to this point.

In 2006, Congress passed the Postal Enhancement and Accountability Act nearly unanimously in both chambers. That is not to say the process was easy; lawmakers had been trying without success for several congressional sessions to get something through.

While Postal Service volume and revenues eight years ago were not in the same freefall they are in today, the mounting competition of the Internet was strong enough to rally support for change. The goal of that bill, however, was not primarily focused on putting USPS on a more robust and profitable path, according to aides and lawmakers who worked on it. Instead, legislators wanted to make it easier to raise prices (a one cent bump for stamps could take up to two years), increase transparency so the agency knew whether it was making or losing money, and shift around burdensome expenses that had been placed on USPS during boom times.

The result, therefore, was a far less controversial bill than the proposals lawmakers are putting forth today. Additionally, says former Rep. Tom Davis, R-Va., who authored the 2006 measure, partisan rancor had not yet reached its current crescendo.

“[Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif.,] and I decided we would work together,” Davis says. “We were looking for a way to get to ‘yes’ instead of looking for a way to get to ‘no.’ ”

So while the bill went through with little resistance -- it even won the support of one of the largest postal unions and most of the nation’s largest mailers -- its shortfalls were quickly made clear.

‘Dated Almost Immediately’

Due to concerns with scoring by the Congressional Budget Office and a zealous desire to keep the reform deficit neutral, President George W. Bush issued several veto threats unless Congress found a way to ensure the bill did not impact the budget.

The result was the prefunding of postal retirees’ health care: the Postal Service would have to make arbitrary payments of around $5 billion annually for 10 years to a newly created fund that would be used in the future to pay for the health care benefits of postal retirees.

The decision made sense at the time, aides and stakeholders say, as the Postal Service was still on relatively strong financial footing and could absorb the costs in stride.

That all changed in 2008 when the Great Recession hit, and mail volume began dropping at an unprecedented rate. The agency borrowed from the U.S. Treasury to make the payments until it hit its statutory borrowing cap of $15 billion, at which point it simply stopped making them, in violation of the law. The result has at best thrust the Postal Service deeply into debt and at worst created what critics call a manufactured crisis that threatens the very existence of the agency.

“Shortly after that bill was enacted, the recession hit and mail volume -- the bottom just fell out,” says a Senate aide who worked on the 2006 bill and continues to work on postal issues today. “The bill was dated almost immediately unfortunately.”

Prefunding is “not a bad idea when you’re making money,” says Frederic Rolando, president of the National Association of Letter Carriers. He adds, however, that no one anticipated the ensuing financial collapse, or that USPS would continue to have to make payments it could not afford.

So while the bills’ architects insist the primary elements of their postal reform worked and better positioned the Postal Service for the ensuing collapse, the legislation has come to be defined by elements that were added as afterthoughts.

In addition to the prefunding requirements, critics point to a rate cap -- necessary to regulate a government-enforced monopoly on mail delivery -- as another of the law’s flaws. It included the opportunity for an emergency rate increase greater than the rate of inflation, which USPS used earlier this year, citing the recession as the emergency. The mailing industry, which fought the rate hike every step of the way and continues to litigate its legality in court, says the recession justification violates the original intent of the bill.

“Two aspects of it, which were not at the core of what the legislation was trying to do, have driven the problems that we’re experiencing since then,” says Rafe Morrissey, vice president of postal affairs for the Greeting Card Association, a key industry that postal officials expect to continue to make up mail volume after the current slide bottoms out.

In response to previous failures of USPS dabbling in non-postal products, the 2006 bill also hamstrung the agency by prohibiting it from providing anything other than mail and package services. From banking to passport photos, nearly all postal reform stakeholders agree any legislation must unchain the Postal Service to leverage its unique, in-every-community network to create new sources of revenue.

Seth Perlman/AP file photo

High Stakes for Unions

Fast forward eight years and you have 200,000 fewer postal jobs since the 2006 bill was signed into law. The Postal Service has slashed its massive 2006 mail processing plant network of 673 facilities by 64 percent. USPS is increasingly hiring part-time employees, meaning non-union, hourly, not-eligible-for-the-full-array-of-benefits workers.

It’s easy to see why labor groups -- which some key lawmakers label as the biggest obstacle in passing postal reform -- are concerned about future cuts.

“We have a [postmaster general] that’s hell bent on privatizing,” says Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers Union. “His approach is to diminish service, diminish standards, and it’s putting the Post Office into a downward spiral that, if it continues, it will not be able to recover from.”

As a result, the postal unions have worked together to make sure the dream of postal reform -- or at least the types of reform the major players in Congress are putting forward -- is never realized. The unions have made their voices heard, both publicly in congressional hearings and behind closed doors in private meetings with lawmakers’ and their staffs, presenting their own visions for the future of the Postal Service, bemoaning the cuts they have already endured and even questioning the negative state of postal finances.

In 2011, for example, postal unions banded together to organize protests outside every district office in the country to vocalize dissent for cutting mail services as a part of any legislative overhaul.

The result? Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are reticent to embrace anything that could anger their constituents, or worse yet, jeopardize key labor campaign funds. All House members have a post office and postal employees in their districts, and all senators have processing plants in their states.

“It’s the unions,” says Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee and author of two USPS bills that cleared his panel this session and one that did so last session, of why it has been impossible since 2006 to even get a bill to the House floor for a vote. “It’s the union stranglehold on these members.” He adds: “Unions are perfectly willing to have the government on the hook for over $130 billion in unfunded liabilities today.”

Unions are wont to beat the privatization drum, an effective scare tactic with their members, who have watched with a careful eye toward Europe as countries like Germany, the Netherlands and, most recently, the United Kingdom, have shifted mailing to the private sector.

Postmaster General Donahoe, employed by USPS for his entire 39-year career, working his way up through the organization from his first job as a clerk, says he has no interest in privatizing the Postal Service.

“Privatization around the postal world has happened because of foolish, short-sighted decisions by different countries to allow their postal services to get in such bad situations the only way out is to privatize,” Donahoe says.

Donahoe grew up in Pittsburgh, where he watched 100,000 of his friends, relatives and neighbors lose their jobs when the steel industry collapsed. He says he is doing everything in his power to ensure a similar fate does not befall the Postal Service, an organization with roots tracing back to the U.S. Constitution. He emphasizes his approach is long-term in nature, and takes solace in the fact he has overseen the agency’s transitional period while ensuring a “soft landing” for postal employees and customers alike.

“Truthfully I’m proud of the fact that we’ve been able to make these changes without laying anybody off,” he says. “Nobody else in this United States has been able to make this many changes with anywhere near the lack of negative impact on their employees.”

Still, Donahoe faces pressure from all angles. The mailing industry and businesses that depend on mail service have united to form the 21st Century Postal Service, which has launched its own lobbying efforts to reform USPS. While unions worry about service cuts that in turn lead to job cuts, mailers concern themselves with getting their products to their customers in a timely and cost-effective manner. (Read: the Postal Service cannot simply increase prices until it begins turning a profit.)

“I think there’s generally a lot of cross communication and sharing of information,” says the Greeting Card Association’s Morrissey of the mailing industry. In recent years, the mailers have attended meetings at the Postal Regulatory Commission, teamed up with labor groups to put forward mutually beneficial proposals and lobbied lawmakers on their own to advance their interests.

An analysis released earlier this year by economist Nam Pham and his research group ndp analytics quickly makes it clear why these groups too have the ear of power players in Washington, D.C. Pham and his team say the entire mailing industry depends on the Postal Service’s networks. He adds sectors such as national security and social safety rely on postal-maintained mapping, address and ZIP code systems, concluding that the success of the U.S. economy depends on the health of USPS.

The industry’s strength was on display earlier this year when Sen. Tammy Baldiwn, D-Wis., typically a reliable Democratic vote, refused to go along with her chairman in the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Sen. Tom Carper, D-Del., and his plan to overhaul the Postal Service. Baldwin was able to successfully delay a committee vote on the bill citing concerns raised by big mailers in her home state, and ultimately did not vote in favor of the bill.

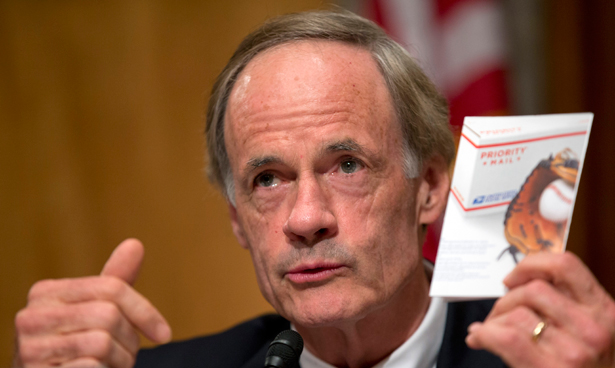

Carolyn Kaster/AP

‘This Place Is Dysfunctional’

Carper’s bill, endorsed by the Postal Service and members of both parties, is generally seen as a compromise, as it would delay, but not prohibit the transition to five-day mail delivery and additional plant closures. USPS attempted to eliminate Saturday mail delivery on its own in 2013, but was rebuffed by a government audit that said an obscure, one-sentence provision in each year’s appropriations bill barred the change. Absent congressional legislation, USPS plans to shutter 82 processing facilities in 2015.

Carper says Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., encouraged him to work with his ranking member, Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., and ultimately the two were able to agree on a proposal.

Carper also led the charge for postal reform in 2012, when -- according to Carper and other Democrats -- the two sides came extremely close to reaching an agreement. He says Senate and House staffs “were able to find common ground more often than not.”

MAP: WHERE THE USPS IS CUTTING 7,000 JOBS.

Issa, Carper’s counterpart in the House, disputes that claim, saying Democrats “were never willing to budge.”

This time around, Carper says he has an “even better compromise than we had two years ago.”

“This place is dysfunctional,” Carper says of the Senate. “[That] doesn’t begin to describe it.” However, he adds that compared with other big issues on the congressional plate, postal reform is “not a slam dunk, but it is in much better shape.”

Ultimately, Carper, who played a crucial role in passing the 2006 bill, would like to fix the problem for good. He says he does not want Congress to be again dealing with overhauling the Postal Service three or four years down the road.

In the House, Issa has proposed eliminating Saturday mail delivery, phasing out to-the-door delivery in urban areas and re-amortizing USPS prefunding so it has to make more manageable annual payments spread out over a longer period of time, while allowing the agency to continue its facility consolidation plan unabated. The White House has largely endorsed those reforms, though not a single committee Democrat has gotten on board.

Most postal stakeholders have balked at those proposals, calling Issa’s measures more extreme than the Senate legislation. Unions say they are willing to compromise, but to date have only endorsed a bill put forward by Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., perhaps the most progressive member of the Democratic caucus.

So that’s the current layout: an unusual marriage of President Obama and Darrell Issa vs. a hodgepodge of Senate Democrats and Senate Republicans across the ideological spectrum vs. labor groups, mailers and liberal Democrats. How can those groups come together to pass meaningful reform? The answer increasingly appears to be simple: they cannot. Illustrating the divide, Issa calls the Senate bill “delusional,” saying it “actually doesn’t do reform.”

The Way Forward

Carper remains optimistic a bill can get through the Senate. A Senate aide, however, says a successful vote requires an extended lame-duck session, which will be determined by how many incumbents are knocked out of office in the November election. In the House, Issa says he will demand a floor vote in the third week of September, but seems resigned to defeat. He notes that 20-30 members of his own party are “unwilling to vote for real change.” The more progressive, less cut-focused labor-backed measures have not even received a committee vote in either the House or Senate.

“I’m the most optimistic person you’ll meet,” says Donahoe of something passing this year, “and I don’t think it will happen.”

Absent a miracle -- in which, in just a matter of weeks after the midterms, the House and Senate pass their respective bills and are able to sort out their fairly drastic differences in conference committee -- it will once again be back to the drawing board next year.

Issa, who is term-limited as oversight chairman, has a bold idea to get the votes needed to pass a bill. Postal liabilities, such as retirees’ health care -- which is now partially funded -- workers’ compensation costs and its existing debt to the Treasury are all currently “off budget,” meaning they do not contribute to the country’s annual deficit. Issa says he will fight to bring those expenses back on budget in an effort to force lawmakers to either vote for postal reform or be held responsible for adding to the national debt.

He says the argument used by postal advocates -- that the Postal Service is a self-funded agency that receives very little in appropriations from the U.S. government -- is misleading, and bringing the agency’s future liabilities on budget is “the only hope” for passing reform.

Others find hope in Issa’s diminished role in the future.

“When you have people like Issa leading the charge you’re going to get outlandish and outrageous legislation,” says APWU’s Dimondstein.

A House aide who worked on postal legislation in 2006, says when comparing Issa to the collaboration he saw then, “So many of the things he has done have been partisan.”

Davis, the former Republican representative who led that charge in 2006, says President Obama also has to step up. Perhaps not surprising with everything else on a presidential agenda, postal issues consistently take a back seat.

Even in the unlikely event Obama prioritized the issue, and a new House oversight chairman ushers in a new era of bipartisanship, a grand philosophical divide still separates postal management from its workforce. Labor groups say USPS would be profitable this year if not for prefunding requirements, which is, for the most part, true. Also true, however, is the Postal Service is currently reaping the benefits of a non-permanent, dramatic price increase, as well as the non-repeatable immediate savings from consolidating plants. And, of course, mail volume will continue its inevitable decline.

For now, the Postal Service will continue to try to address the problem in the only way it can -- through cuts, consolidations and workforce reductions, as well as pushing forward in growth areas such as packages and direct mailings -- while waiting for the gift of reform that Congress never seems inclined to give.

“We’ve taken a lot of costs out of the system, but we’ve never been able to catch up,” Donahoe says of the agency’s internal efforts to deal with the ever decreasing mail volume. Still, the postmaster general remains optimistic: “We’re not going to put the white flag up.”