jeshoots.com

A Behavioral Economist Tries to Fix Email

Inbox maintenance was taking up a lot of Dan Ariely’s time, so he decided to study it as he would anything else.

Can anything be done to make people happier with their jobs? What can prevent people from overeating? Will people like beer with balsamic vinegar in it just because they’ve been told it contains a “secret ingredient”?

These are some of the questions that Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist at Duke University, has studied in his research over the years, which spans in scope from the weighty to the quotidian. He has attempted to puzzle out the intricacies of human motivation and decision making, and two threads that come up often in his research are why people so often make choices that leave them worse off, and how tweaking small things might ward off needless, irrational suffering.

So when he realized that reading and sending emails was consuming an ever-expanding portion of his time—Ariely regularly receives hundreds of emails a day, excluding spam—he wondered if there were something he and others could be doing differently in managing their online correspondence. What small behavioral tricks could he deploy to make the whole ordeal less stressful?

“Everybody recognizes how much we are destroying productivity with the current [way we] email,” Ariely told me. The consulting firm McKinsey estimates that knowledge workers spend a little over a quarter of their workdays managing email, and Ariely was drawn to thinking critically about something that so many people spend so much of their days on. “I care about the ways in which we mismanage our health, mismanage our money, and mismanage our time,” he says. “From all of those, time is probably the easiest place, not to optimize perfectly, but to make some substantial improvements.”

One feature of email that seemed to leave room for improvement is the fact that every new message, whether vitally urgent or completely worthless, warrants an immediate ping. This, despite the fact that most people have a hard time ignoring messages as they arrive. In a 2002 paper, for instance, researchers found that for 70 percent of messages, it took workers an average of only six seconds to react to a notification indicating an email was unread. (Perhaps, 15 years later, that average time has even gotten shorter.) And these interruptions come at a steep cost (in terms of both productivity and stress), as it takes a while for people to return to the task they were originally doing when they were made aware of the message’s arrival.

“The first thing we should question is this idea that all emails are created equal,” Ariely says. “Should each email be able to interrupt people? Is the email from someone’s boss as important as the weekly industry newsletter he’s signed up for?” To get a sense of the answer to these questions, he posted a survey on his blog asking respondents to review the last 40 emails they’d received, saying for each one how long they could’ve waited to read it: Right away? Two hours later? A week later? Never?

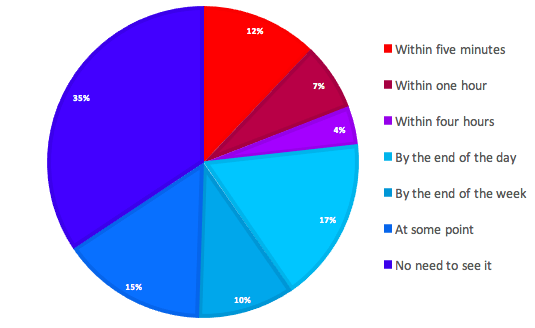

What he found was that roughly a third of messages did not clear the bar of needing to be seen at all, and only about a tenth of emails were considered important enough to need to be read within five minutes of receipt.

How Soon Does Any Given Email Need to Be Seen?

When asked to sort 40 recent emails by time-sensitivity, Ariely’s respondents said that the majority were not urgent.

In this data, Ariely saw an inefficiency to target. Even though every email, by default, triggers a notification, it’s unlikely that any given email deserves one. So, with the help of some software developers he’d worked with in the past, he tried to come up with a way to tweak the default settings that are baked into email. The result of that work is Filtr, an app that lets users make simple rules, based on the sender, about when an email will show up in their inbox. For example, users can set it up so that emails from family members show up immediately, but non-time-sensitive newsletters show up all at once, at the end of the day.

Ariely hasn’t done any widespread user-satisfaction surveys, but he says that so far Filtr is at the very least making his own digital life less exasperating. “Being able to filter it, and say, ‘Okay, those are the small subset that are actually important to get to, and the rest can wait,’ is a huge improvement to my well-being,” he says.

It’s possible that his anecdotal relief could have wider implications for other distressed emailers. “I think Dan’s idea is really intriguing,” says Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at University of California, Irvine. Mark, who has published several studies demonstrating the toll that email-related stress takes on workers, would want to study Filtr’s effectiveness before arriving at any conclusions. But she finds the idea promising because it restores a degree of control, the loss of which she says is one of the main reasons people get stressed about email. “I think if people felt they had more control over their information, over their time, they would be a lot less stressed,” she says.

Ariely’s curiosity about email has not just led him to help create Filtr, but also Shortwhale, a web app that makes emails arrive in a form that’s easier for recipients to process. Sending a message to someone who uses Shortwhale means being directed to a webpage with a few questions such as “How urgent is this?” and “Do you need a reply?” In the form where senders are to enter their messages, they’re prompted to “Go straight to the point” and are encouraged to “Make this a multiple choice question” if possible.

Ariely, who is a happy user of Shortwhale, says that this additional information has been a boon because he normally would receive a high volume of email but little in the way of useful context. “What I’ve learned through Shortwhale is there are lots of ... people who just want to send me things and say, ‘just for your information.’ And it’s so good to know what people have in mind.”

The system, which Ariely says has a very small user base, does have its downsides. “There’s something a little bit obnoxious about Shortwhale, in the sense that you say, ‘When you write me, please write me this way,’” he says. “That puts more burden on you as the sender... I have to say that when I started with this, the arrogance involved in it really bothered me.” And besides, for the concept of Shortwhale to be truly powerful, it would need to be integrated into the email clients that everyone uses. “Just imagine how much sense it would make if the person who sent you an email had a way to very quickly tell you that for this email, they need a response within a week, or ‘no response necessary,’” he says. From his surveys, Ariely had learned of an expectations gap between senders who didn’t need responses and recipients who thought they might.

For now, Filtr and Shortwhale both remain niche widgets that dutifully serve the needs of their creator and a small handful of high-volume emailers who, like him, have gone out of their way to adopt them. But in Filtr, Gloria Mark, the informatics professor, sees the seed of a powerful idea—“batching,” or checking email at set times, in batches—that, if fleshed out and taken up more widely, could make countless people much less stressed out about email.

There are two different types of batching, the first more well-known than the second. Productivity bloggers extol the virtues of this first type of batching, which consists of checking email only at set times and handling them all at once, as opposed to addressing each one as it comes in. It is an appealing idea, and many are no doubt drawn to it because it appears to eliminate distractions. Whether it actually leaves people better off is hard to determine: When Mark studied this behavior, she found that batchers who received a lot of email rated themselves as more productive, but were no less stressed.

There is a second type of batching, one that Mark believes would get to the root of email-related stress. “I’ve argued for years, and I’ll explain why, that the organization should batch emails,” Mark says. What she means is that a company could set it up so that when emails are sent, their delivery is postponed until the next batch-delivery time. Mark imagines a situation where emails arrive in three waves: at the beginning of the day, after lunch, and at the end of the day. “The logic for doing that is because then everybody’s expectation is that emails only come three times a day,” she says, adding, “Everybody knows that everybody’s getting emails at a certain time.” The insight here is that what really makes email so stressful is the social expectation of a quick response—something individual batchers don’t have control over, but something an employer could.

Mark’s ideal system does allow for urgent communications, just not through email. If workers need to contact one another with time-sensitive requests, she says, they’d pick up the phone, send an instant message, or talk in person.

Her solution, though elegant, is probably not likely to catch on anytime soon, because it’d require rewriting the digital-communication social contract. Lately, though, Mark says that in her life, email hasn’t been the prominent stressor it once was. These days, it’s something else. “I find myself checking the news every break that I get,” she says. “It’s replaced email by a long shot.”