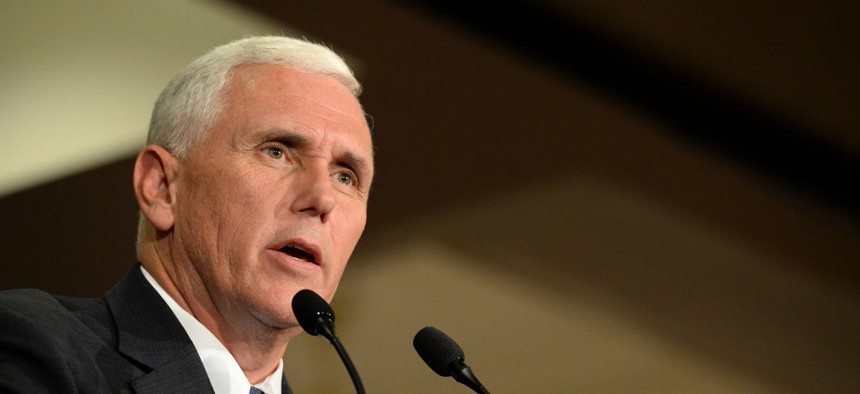

As Indiana governor, Mike Pence oversaw performance management policy for civil servants. Gino Santa Maria/Shutterstock.com

Pay for Performance Could Be Coming to Federal Agencies

Vice president-elect Mike Pence was governor of a state with a strong commitment to rewarding good performance.

President-elect Donald Trump commands the spotlight now, but our next vice president is likely to play a central role in the new administration’s plans for federal agency management. As is typical of chief executives, Mr. Trump is not known for digging deeply into day to day operational issues. Added to that are the business executives mentioned as possible Cabinet officers (“CEO-Heavy” was in one headline). When the Trump Cabinet meets, its likely they will agree on the approach to planning and managing performance.

In a July column on President-elect Trump’s plans to reform the Veterans Affairs Department, he was quoted as planning to “financially reward employees who do a good job, and fire those who don’t.” That of course would be common among business executives. The philosophy is undoubtedly shared by the business executives who might join his administration.

What has not made the headlines is that that the vice president-elect, Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, was chief executive of a state that has had a pay for performance policy since 2006.

The state has a similar policy for public school teachers; it’s one of a handful of states now rewarding teachers for student performance. There may be no other state that has made a stronger commitment to rewarding good performance. For 2016, state employees who met expectations got a 2 percent increase, those exceeding expectations received 4 percent, and those who were outstanding received a 6 percent increase. That is at least as generous as the typical company.

In the discussion of Mr. Trump’s plans for the VA he also stated that “One of the most important reforms we can make is accountability.” He complained that “outdated civil service rules” prevented leaders from disciplining problem employees. Now with his party in control he may be inclined to do something about that. Accountability is so deeply entrenched in business thinking that it’s taken for granted and rarely discussed. Mr Trump’s comments, along with quotes from people who have worked for him, suggest he will make increased accountability a priority.

Accountability is reinforced by performance pay. Financial rewards are explicitly tied to performance. The failure to earn a bonus or salary increase sends a powerful message.

The hurdle is that government is not business, and does not have the same “team” commitment to making organizations successful. In business, that focus is reinforced by financial incentives, stockholder pressure and the business media that publicizes corporate successes and failures. In contrast to government, companies rarely reward executives or managers for individual performance. Companies have increased the importance of incentives over the past two decades.

Added to this is Indiana’s business-like approach to planning and managing performance. It’s based on the textbook use of cascading performance goals linked to each agency’s strategic plan. The state relies on the widely used SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant or Realistic, and Time Bound) framework for goal setting. Employee performance ratings are based on a combination of goal achievement and an assessment of job-related competencies.

Additionally, the phrase “continuous improvement” is used in state handbooks in discussions of performance management. The idea is frequently used in business but it requires a commitment to empowering employees and depends on a readiness to refine or modify plans as the year unfolds.

All of this is common in business; corporate executives who accept leadership roles in agency management will be accustomed to relying on this general approach to management.

State administrators in Indiana had six years to work out the kinks in the performance management process and in managing pay increases before Mr. Pence began his tenure as governor. It’s likely any problems were addressed while Pence was in Congress, before he became governor, so he may not fully appreciate how much effort was required. Unions have a presence in Indiana’s government but are far less powerful than in many northern states.

Assessing Performance

An important related trend in the private sector is the new direction unfolding in the process used to guide and assess individual performance. The impetus to change was the widely acknowledged dissatisfaction with year-end performance appraisals and rating practices.

With previous columns, when the prospect of pay for performance is mentioned, reader comments argue, to state it bluntly, that managers cannot be trusted to handle this responsibility. It’s not clear if the concern is shared widely but that is essentially the same reason dissatisfaction is high in the private sector. Few employers have done a good job of preparing managers or of holding them accountable.

But new thinking is gaining acceptance. A few companies are reported to have eliminated ratings but experience in both sectors confirms employees find that less satisfying. Government tried pass/fail years ago and it was very unpopular—it does nothing to help employees perform better.

The best practice today addresses two core problems:

First, the emphasis has shifted to frequent, informal coaching. The analogy is coaching during a football or basketball game. It requires a different set of supervisory skills. It’s important also because with ongoing feedback, year-end ratings are not a surprise.

Second, to minimize possible bias and discrimination, employers are switching from the traditional supervisor-controlled ratings to ratings by committees of peer level managers. A recent article described the way committees of Facebook managers handle ratings: “Managers sit together and discuss their reports face-to-face, defending and championing, debating and deliberating, and incorporating peer feedback.” The ratings generated in those discussions are accepted as fair and consistent across an organization. The company has a formula that links ratings to financial rewards.

Moving to pay for performance will unquestionably be difficult. It will require commitment at the highest levels. The commitment must include adequate training for managers. There is also a need to review experience and address problems each year. Indiana, along with other state and local government employers, proves it can be successful.

Mr. Trump appears to like big ideas. Scrapping the General Schedule system—and, with adequate planning and preparation, replacing it with a system based on proven, best practices—would benefit government.

Image via Gino Santa Maria/Shutterstock.com.