Pavinee Chareonpanich/Shutterstock.com

Report: Happiness Won't Help You Live Longer

A new study of hundreds of thousands of women finds no difference in mortality between the happy and the unhappy.

With apologies to the hundreds of machines pressing self-help books at this very moment that preach the life-changing benefits of happiness, it is incumbent upon me to say: It will not save you from death.

Of course it won’t! Death comes to us all, be we smiling or crying. But there have been numerous studies in recent years suggesting that happier people may live longer and that happiness could even help protect against some health problems, like heart disease.

According to a massive new study published in The Lancet, happiness has no such power. The data came from the Million Women Study in the U.K., which surveyed a million women between the ages of 50 and 69 (though only about 720,000 were used in this analysis). Three years after joining the study, the women filled out a questionnaire about their happiness, and during 10 years of follow-up, electronic records let the researchers know how many died, and how.

Being in ill health was associated with unhappiness (being sick is not fun), so the researchers excluded women who had already had cancer, heart disease, strokes, or chronic obstructive-airway disease. That way, they could see if it was unhappiness alone that made people more likely to die.

It did not.

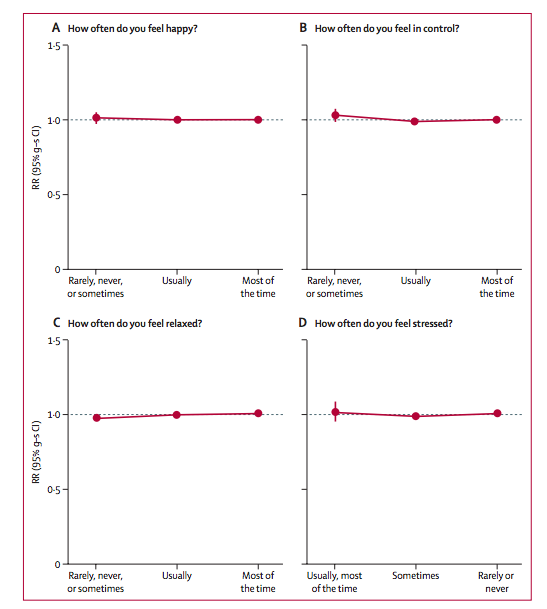

This chart shows the risk of mortality based on how the women who started in “good or excellent health” answered questions about happiness, feeling in control, relaxation, and stress.

Self-Reported Happiness and All-Cause Mortality

The line at 1.0 is “sort of average” with regard to mortality risk, says Richard Peto, a co-author on the study and a professor of medical statistics at Oxford University. As is clear from the chart, there was no difference in risk of death based on how people answered these questions.

Peto believes that the previously established connections between unhappiness and earlier death were actually “reverse causality,” in which unhappiness was a byproduct of the illnesses that led to death.

“In our view, the previous studies haven’t been well done,” he says. “All that’s going on is ill health actually was causing unhappiness and stress. There’s a pathetic old joke, where the question is ‘What's the most dangerous place in the world to be?’ and the answer is ‘Bed, look at the number of people who die in bed.’ Well, that's just a pathetic old joke, but that’s reverse causality.”

In an initial analysis, the Lancet study did find an association between mortality and unhappiness, but that association disappeared once they adjusted for baseline health.

“I think the interesting implication is we’ve got very few things that really matter as far as health is concerned,” Peto says. He names smoking and obesity as two things that are very good predictors of mortality. But unhappiness, it seems, is not at all on their level.

“You could say it’s good news for the grumpy,” he says.

(Image via Pavinee Chareonpanich/Shutterstock.com)