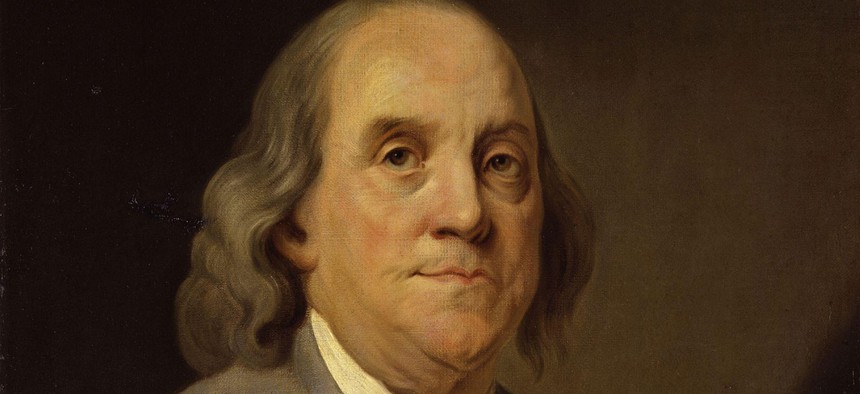

The Joseph Siffrein Duplessis portrait of Benjamin Franklin c. 1785, sits in the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery. National Portrait Gallery

How Americans Lost Track of One Founding Father's Definition of Success

According to Benjamin Franklin, what mattered in business was humility, restraint, and discipline.

When he retired from the printing business at the age of 42, Benjamin Franklin set his sights on becoming what he called a “Man of Leisure.” To modern ears, that title might suggest Franklin aimed to spend his autumn years sleeping in or stopping by the tavern, but to colonial contemporaries, it would have intimated aristocratic pretension. A “Man of Leisure” was typically a member of the landed elite, someone who spent his days fox hunting and affecting boredom. He didn’t have to work for a living, and, frankly, he wouldn’t dream of doing so.

Having worked as a successful shopkeeper with a keen eye for investments, Franklin had earned his leisure, but rather than cultivate the fine arts of indolence, retirement, he said, was “time for doing something useful.” Hence, the many activities of Franklin’s retirement: scientist, statesman, and sage, as well as one-man civic society for the city of Philadelphia. His post-employment accomplishments earned him the sobriquet of “The First American” in his own lifetime, and yet, for succeeding generations, the endeavor that was considered his most “useful” was the working life he left behind when he embarked on a life of leisure.

Franklin was aware that this assessment was a possibility, and so were his peers. One of them implored him to publish the account of his life, declaring in a letter that his tale of bootstrapping success would be uniquely informative to “a risingpeople.” It had the “chance,” the correspondent said, of “improving the features of private character, and consequently of aiding all happiness both public and domestic” in the breakaway colonies. Rather than shrink from such lofty expectations, Franklin embraced them, and, in a grinning gesture of marketing shrewdness, inserted the text of the letter between the first two parts of his memoir.

Written in a little over a week when the 65-year-old Franklin was taking a break from traveling the British Isles, collecting honors and trying to quell the growing hubbub between England and her colonies, the first of these sections would become the most famous part of the Autobiography. It provided the origin story of America’s most famous tradesman and how he emerged from the “Poverty & Obscurity” in which he was “born & bred.”

The story begins in Boston, familiarly enough, with an ambitious father who longed for a better life for his son. In this instance, that meant better than the putrid profession of a tallow chandler, the vocation to which Josiah Franklin had dedicated himself. Ben was the fifteenth of seventeen children and the youngest of Josiah’s boys. As such, the elder Franklin planned to offer him “as the tithe of his sons, to the service of the Church.”

A minister’s education proved too expensive, however, so Ben entered a stationer’s shop to learn a trade. He was only 12 years old, and if he felt newly enrolled in the school of hard knocks, it was because they were generously applied by his older brother James, the proprietor of the printing house where he apprenticed. Understandably, the two did not get along well, and James grew increasingly impatient with his brother, whose genius, by turns, enriched and embarrassed him. After five years and one last falling out, the younger Franklin ran away to Philadelphia, arriving after a perilous sea journey with only one “Dutch dollar, and about a shilling in copper.”

In Philadelphia, Franklin eventually became the proprietor of his own printing house, intent on securing his reputation as a tradesman. “I took care not only to be in Reality Industrious & frugal,” he says in perhaps the most telling passage of the Autobiography,

but to avoid all Appearances to the Contrary. I drest plainly; I was seen at no Places of idle Diversion; I never went out a-fishing or shooting; a Book, indeed, sometimes debauch’d me from my Work; but that was seldom, snug, & gave no Scandal: and to show that I was not above my Business, I sometimes brought home the Paper I purchas’d at the Stores, thro’ the Streets on a Wheelbarrow. Thus being esteem’d an industrious thriving young Man, and paying duly for what I bought, the Merchants who imported Stationary solicited my Custom, others propos’d supplying me with Books, & I went on swimmingly.

Franklin was just 22 and his greatest successes were all still before him, but as far as future generations would be concerned, the legend of the colonial upstart was largely complete.

* * *

When an ailing Franklin put down his quill once and for all sometime around Christmas of 1789, what he had accomplished only took readers through his early 50s. That meant the Autobiography was weighted toward his early years as a striving stationer, showcasing, as he explained to a friend, “the effects of prudent and imprudent conduct in the commencement of a life in business.”

Despite being a truncated account, the book was a sensation. In the United States, no fewer than 22 editions of the Autobiography were published between 1794 and 1828, often coupled with The Way to Wealth and other of Franklin’s writings that underscored the lessons he learned as a young shopkeeper. Over the course of the 19th-century, the Autobiography became a book of wisdom for working people, a model for new Americans, and a companion piece to the Bible in some grammar schools intent on moral instruction. By the end of it, William Dean Howells, the celebrated author and editor of The Atlantic, spoke for a nation when he called Franklin “the most modern, most American, of his contemporaries.” So did then-Princeton professor Woodrow Wilson, who described the Autobiography as “literature with its apron on, addressing itself to the task, which in this country is every man’s, of setting free the processes of growth.”

Franklin’s memoir became for Americans the original book about success in business, and Franklin himself the colonial Dale Carnegie. He put forth an ideal of restraint and industriousness. Consider the most famous episode in theAutobiography, Franklin’s account of the “bold and arduous Project of arriving at moral Perfection.” Not long after opening his printing house, the young tradesman decided that he “wish’d to live without committing any Fault at any time.” He consulted the advice of a wide variety of authors until he finally derived 13 virtues to live by. To each one he appended a “short precept,” creating a list to confront his conscience and, later on, his readers. Here are virtues four through six:

4. RESOLUTION.

Resolve to perform what you ought. Perform without fail what you resolve.

5. FRUGALITY

Make no Expence but to do good to others or yourself: i.e., Waste nothing.

6. INDUSTRY.

Lose no Time.—Be always employ’d in something useful.—Cut off all unnecessary Actions.—

The other virtues on Franklin’s list were Temperance, Silence, Order, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity, and Humility. Taken together, they describe a young businessman who was both exceptionally driven and entirely abstemious, one who always preferred to reinvest his earnings rather than enjoy them.

F. Scott Fitzgerald had hinted at this before, near the end of The Great Gatsby. After Gatsby’s death, his father, “a solemn old man,” arrives from small town Minnesota. When he sizes up his son’s sprawling estate, he wants the narrator of the novel, Nick Carraway, to appreciate “Jimmy’s” humble origins and spirit of self-improvement. He presents Nick a dog-eared copy of Hopalong Cassidy and opens it to the back to reveal, in boyish scrawl, a Franklinesque regimen. “On the last fly-leaf was printed the word Schedule,” Nick says, “and the date September 12, 1906, and underneath:

Rise from bed. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.00 a.m.

Dumbbell exercise and wall-scaling. . . . . . 6.15-6.30 ”

Study electricity, etc. . . . . . . . . . . . 7.15-8.15 ”

Work. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8.30-4.30 p.m.

Baseball and sports. . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.30-5.00 ”

Practice elocution, poise and how to attain it 5.00-6.00 ”

Study needed inventions. . . . . . . . . . . 7.00-9.00 ”

General Resolves No wasting time at Shafters or [a name, indecipherable] No more smokeing or chewing Bath every other day Read one improving book or magazine per week Save

$5.00$3.00 per week Be better to parents

The irony of this adolescent self-improvement regimen does not escape Nick. It is not that they were altogether unnecessary to Jay Gatsby’s ascent or even that his extravagant lifestyle is clearly odds with them. Rather, it’s that, by the time Gatsby has “arrived,” he is entirely convinced that, pace Franklin, decadent behavior is not only the calling card of success but the best guarantee of its continuance.

* * *

Even if Fitzgerald didn’t explicitly aim to provide a counter-narrative of commercial advancement, the character of Gatsby fits nicely with an archetype exampled from the Gilded Age to Gordon Gekko, one that is less an antihero of capitalism than an alternative to Franklin’s ideal.

Among business-school students, it is also the one that commands the most attention. When I assign passages from the Autobiography to my business-ethics classes, many students regard Franklin as they would an eccentric neighbor who knows more than he’s letting on. The vision of capitalism he embodies is not altogether alien to them, and they often grant that his memoir might be a successful primer for a sterling career in middle-management (a backhanded compliment that invites the reminder that they are, after all, working toward a Master’s degree in “Business Administration”). Yet, for the most part, many students seem convinced that the example of Franklin does not lend itself to realsuccess or the sense of pride consistent with it.

And maybe it doesn’t—at least not if we are talking about a definition of success that Ben Franklin never intended. Not long after he retired to his life of leisure, Franklin wrote his mother to say that he hoped the more likely tribute paid him after his death would be “He lived usefully, than, He died rich.” Of course, mothers like to hear such things, giving sons good reason to say them. But if Ben was describing a commitment that is flattering in theory because it is rarely favored in practice, the degree to which his life reflected it helped distinguish him from the other Founders, whose ambitions more nearly resembled those of an American aristocracy. Among them, the historian Gordon Wood has said, Franklin was not only “the most benevolent and philanthropic,” given that he affirmatively walked away from business at the height of his earnings potential, he was also “in some respects the least concerned with the getting of money.”

Ultimately, for Benjamin Franklin, the question of how to succeed in business could not be divorced from how to succeed in life and, therefore, the ends to which one should live. To live like a king seemed distinctly un-American. To live for no one else seemed unimaginable. If Americans view things differently today, perhaps that says less about how we succeed in business than what we believe it means to lead a life well lived.