Why Budget Forecasts Should Include the Next Big Disaster

Four things agencies need to know about creating climate resilient facilities.

The White House made a bold move last week to minimize the economic burden of climate change. Specifically, the Office of Management and Budget is asking federal agencies via the revised Circular A-11 to “consider climate preparedness and resiliency objectives as part of their FY17 budget requests for construction and maintenance of federal facilities.”

This new guidance represents a fiscally astute move on behalf of the administration. Regardless of your beliefs on climate change, the frequency and magnitude of disasters is increasing both nationally and globally. The glaciers are melting, the seas are rising and chronic drought is becoming a way of life for many parts of the country.

Preparing our federal facilities to address the shocks and stresses of the 21st century makes sense. It will save the U.S. taxpayer billions of dollars and will allow the government to execute mission-critical functions more reliably in times of distress.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center for Environmental Information, the U.S. has sustained 178 climate-related disasters since 1980, in which costs exceeded $1 billion. The total cost of these events is north of $1 trillion. In 2014 alone, there were eight weather and climate-related events with losses beyond the $1 billion mark across the U.S.

The global footprint of government-controlled facilities is mind-blowing. It is the nation’s largest landlord with nearly 900,000 buildings or structures in its control. The Defense Department manages a jaw-dropping 560,000 facilities globally. Many of these assets, and the missions they support, are highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change—namely sea-level rise, hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, wildfires and drought.

OMB’s new budget requirement will present unprecedented challenges for agencies as they plan routine construction and maintenance projects across the globe. Most agencies lack a reliable risk analysis capability; the field of resilience is still maturing and the scope of the problem is daunting.

There are a handful of tips that will be useful for agencies to consider as they begin to prepare their facilities for climate change and extreme weather-related events.

Here are my top four:

- Understand What It Means to Be Resilient

The definition of resilience is “the ability to anticipate, prepare for, and adapt to changing conditions and withstand, respond to and recover rapidly from disruptions.”

In the context of federal facilities, becoming more resilient might involve a number of different solutions—everything from relocating facilities in disaster prone areas to operating more efficiently to conserve scarce water and energy resources.

Resilience is often confused with “hardening.” Gone are the days of simply building taller walls; good resilience practitioners have the ability to anticipate the future and masterfully blend cost, benefit and function to create the best mix of solutions.

In many cases, resilience solutions can have dual benefits.

For example, when Superstorm Sandy’s 14-foot storm tide nailed Hoboken, New Jersey, on Oct. 29, 2012, the streets—according to Mayor Dawn Zimmer—filled with water “like a bathtub.” The storm caused more than $250 million in damage. Over 80 percent of Hoboken was flooded and businesses saw a 60 percent drop in revenue a month after the storm.

The initial reaction was to erect giant sea walls around Hoboken—but citizens cringed at the thought of giving up their magnificent views of New York harbor and Manhattan skyline.

Perspectives changed when the city began working with a winning team from Rebuild by Design, a competition created in the wake of the storm to pioneer ways of designing, funding and implementing a resilient future. Instead of erecting big, ugly sea walls, the team created a system of parks, buildings and greenways as barriers against flooding, as well as a park around the city to serve as a rainwater storage site. This is a great example of improving quality of life now while preparing for climate-related events in the future.

- Location, Location, Location

It doesn’t take a Nobel Laureate to understand that some federal facilities are more likely to be affected by climate change than others. Luckily, we have a tremendous amount of resources at our disposal to anticipate those areas that will be hit the hardest. And perhaps more importantly, those areas that will be affected the least.

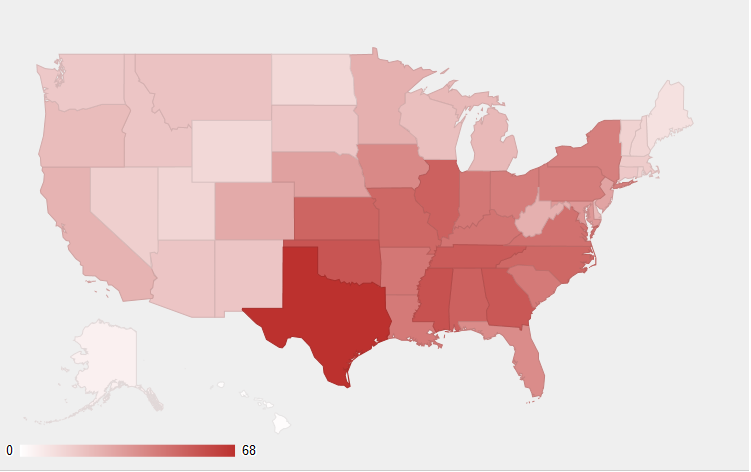

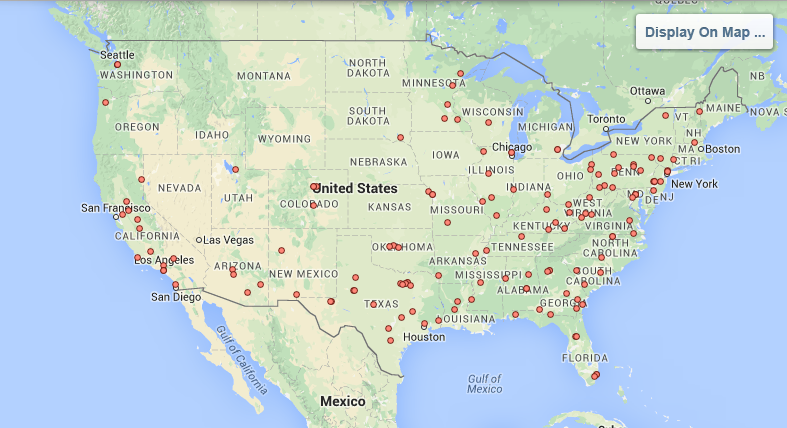

In some cases, history can be a lousy indicator of the future. However, in the game of predicting extreme weather events, history is arguably our best resource. For example, simply overlaying a map of the federal prison system against the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s map of billion dollar weather events since 1980 can be very enlightening. Where is the Federal Bureau of Prisons vulnerable to climate change?

Here are a few resources federal agencies need to become very familiar with as they prepare fiscal 2017 budgets:

- U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit: A huge resource assembled by the Office of Science and Technology Policy and the Council on Environmental Quality. The Toolkit “provides scientific tools, information and expertise to help people manage their climate-related risks and opportunities, and improve their resilience to extreme events.”

- NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center: The go-to source to understand climate forecasts in the U.S.

- United Nation’s World Meteorological Organization: The optimal starting point for understanding climate change trends globally.

- Designing Resilient Buildings 101

There are a number of strategies that need to be considered when constructing a resilient building. Here are a few basics:

Design buildings for high-risk scenarios. Basic risk analysis can uncover those high-probability, high-consequence events that might affect federal facilities in different parts of the country. If the concern is flooding, elevate or relocate. If the concern is earthquakes, strengthen structural interconnections or add new lateral force elements. When appropriate, select sites for new facilities that are not prone to extreme weather or natural disaster events.

An extraordinary new resource to help understand solutions for resilient buildings and other types of infrastructure is the National Institute of Standard and Technology’s Community Resilience Guide. The guide is in draft form, but is expected to be published soon.

Design buildings that conserve energy and water. Climate change requires us to develop new and innovative ways to conserve energy and water.

To save energy, buildings should be designed to maximize the use of daylight. They should also include highly insulated building envelopes, alternative energy sources, and high-efficiency lighting where needed.

From a water perspective, it is estimated that water and sewer costs federal facilities between $.5 billion and $1 billion annually—this will only increase as water resources become scarce due to climate change. To conserve water, facilities should use high efficiency fixtures and eliminate leaks. They also should employ the Energy Department’s Best Management Practices for Water Efficiency.

Design buildings that can be constructed and maintained with local materials and labor. Global climate change will likely result in increased material expenditures, due mostly to higher energy and transportation costs. Materials might also be more difficult to acquire in the future. Agencies should “go local” where possible.

Construct buildings that are durable and withstand a variety of hazards. Agencies must select materials and construction methods that will stand strong in the face of extreme weather conditions.

Relocate mission critical services within a building. Project Legacy, an innovative 1.6 million-square-foot Veterans Affairs Department hospital designed for New Orleans, is moving critical functions like heating, cooling, water and food preparation to higher floors. In addition, emergency rooms are located on the fourth floor, well above the 20-foot flood line. Less essential functions are located on the lower, more vulnerable floors.

- Use Systems Thinking

Federal agencies rely on a network of complex, interconnected systems to execute their missions. Think of a human body—a harmonious balance of cardiovascular, skeletal, respiratory, and cognitive functions. Each system is dependent on the next and is easily stressed when unbalanced or shocked after trauma.

For example, how might chronic drought increase the frequency of blackouts? How might blackouts affect mission critical cyber functions?

Similarly, an agency might have highly resilient facilities, but rely on fragile transportation networks to get their employees to work.

Agencies must understand the systems enabling the execution of mission critical functions—to include the cascading effects of disruptions. This understanding, in turn, will enable them to make sound decisions to improve the resilience of their facilities.

The good news is that advancements in the field of systems thinking, combined with good data and analytics, are allowing us to begin to understand the relationships between different systems for the first time in history. Armed with this understanding, we can create imaginative solutions that give us the biggest bang for our limited resilience-enhancing resources.

While OMB’s budget guidance might be difficult for agencies to execute in the near term, it’s a step in the right direction. Scientists continue to assert that frequent, high-intensity storms, drought and rising temperatures will continue to be the norm, not the exception. Let’s get ahead of the curve and minimize the economic and mission impacts of Mother Nature’s wrath.

Charles Rath is president and CEO of Resilient Solutions 21. He was formerly a principal at Sandia National Laboratories in the area of critical infrastructure resilience and consulted with federal agencies and the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities Challenge.

NEXT STORY: Change It Up This Week