Baseball is one of the few industries where left-handed people make less money. Aspen Photo/Shutterstock.com

Why Lefties Make Less

They've been subtly discriminated against since biblical times, but modern data suggests a significant gap in earnings.

There’s a stereotype that left-handed people are clumsier, but that might have something to do with the fact that they live in a world of objects optimized for the right-handed: scissors, the computer mouse, surgical tools, and guns, to name a few. The discrimination against the 12 percent of the population who are lefties has disarming historical roots. In the Middle Ages, left-handed writers were said to be the devil’s voice boxes, and the Jewish scholar Maimonides included sinistrality in his list of 100 imperfections that should preclude someone from priesthood.

The roots go even deeper, into language. To be dexterous is to be adept, or to be right-handed; the meaning of the English word sinister can be traced back to the Latin sinistra , meaning “left.” The word carries ominous connotations in French, German, Italian, Russian, and Mandarin too.

Left-handed people, it turns out, aren’t just at a cultural disadvantage—they’re at a cognitive one. There’s an urban legend—probably based on the (ultimately quite spotty) findings of a 1995 study —that left-handed people are more inventive, and as proof people point to the fact that four of the last seven American presidents have been left-handed.

In fact, the data suggests the opposite: Lefties score lower on cognitive tests and are 50 percent more likely to have behavioral problems and learning disabilities (such as dyslexia). Also, people suffering from schizophrenia are more likely to be left-handed than are people without the condition.

The little research that’s been done about the financial fates of left-handed people has mostly played into the narrative that they’re abnormally creative and forward-thinking. A 2006 paper and another in 2007 both indicated that lefties out-earned righties, suggesting margins of four percent and 15 percent respectively.

In the Fall 2014 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives , Joshua Goodman, an assistant professor at Harvard's Kennedy School, has a paper that aligns the research with the documented obstacles that left-handed people face. In the paper, “The Wages of Sinistrality: Handedness, Brain Structure, and Human Capital Accumulation,” Goodman identifies statistical shortcomings in previous studies of left-handedness and introduces other figures for analytical poking and prodding. He analyzed five longitudinal data sets (three from the U.S. and two from the U.K.) that have been tracking the lives of babies for decades.

His conclusion? Left-handed people earn significantly less than right-handed people.

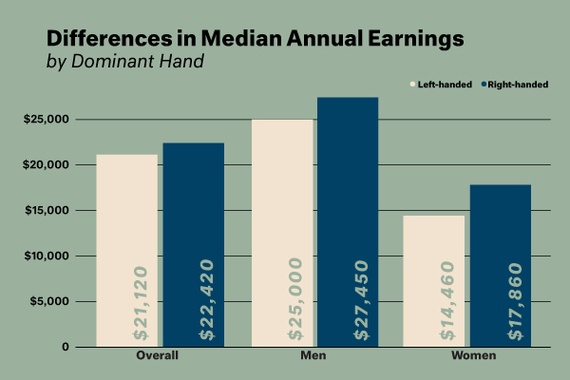

Data: Joshua Goodman; Chart: Elisa Glass/The Atlantic

Lefties’ median earnings are about 10 percent lower than those of righties, which is the same magnitude as the salary hit that comes with spending one fewer year in school. (Speaking of education, left-handed people are also less likely to complete college.) While median annual earnings for righties and lefties differ by $1,300, the dominant-hand gap is even more pronounced when the data is split by gender: among men, it’s $2,500, and among women, it’s $3,400. (Since men are more likely to earn more and also more likely to be left-handed, the gender-specific data yields gaps that are different from those in the overall data.)

What could explain this discrepancy? It would seem that lefties might earn less because they’re at a physical disadvantage when faced with objects made for righties. But that doesn’t seem quite right, as Goodman found that lefties are more likely to work in manual jobs. Instead, it’s probably because of the cognitive problems that, statistically speaking, are more likely to affect lefties than righties.

Determining why those disadvantages arise is more difficult—there doesn’t seem to be one clear cause of left-handedness. It would appear that the trait is at least partially genetic. A child is 50 percent more likely to be left-handed if his or her mother is, and the trait might be derived from the structure of a baby’s brain. But there are other, non-genetic explanations that account for these facts: Children with left-handed mothers might just be more likely to imitate them, and a stressful prenatal environment might force some left-hemisphere functions to migrate to the right side of the brain in utero. Either way—nature or nurture—handedness is a trait that, from the time of birth, appears to have long-term effects on personal economic well-being.

So, between medieval persecution and modern-day wage discrimination, how have lefties managed to stick around since biblical times? For once, research points convincingly to the conclusion that they have an evolutionary advantage—or at least they might have, hundreds of years ago.

In 2005, Proceedings B published a paper theorizing that left-handedness persisted in the pre-modern world because it offered a select few people an upper hand in combat (a punch from an unusual angle can be difficult to guard against). The researchers, Charlotte Faurie and Michel Raymond, analyzed data from societies that still settled conflicts with fisticuffs . The numbers strengthened their theory: 22.6 percent of the Amazon-dwelling Yanomamo people (annual murder rate: four people killed out of 1,000) were left-handed, while only 3.4 percent of the Dioula-speaking people of Burkina Faso (murder rate: 0.013 per 1,000) were lefties.

It’s an elegant (perhaps too elegant) explanation for why left-handedness is still around. But these days, sadly, their only obvious physical advantages lie where using their dominant hand is less expected—in baseball, boxing, and tennis.

( Image via Aspen Photo / Shutterstock.com /em>)