USS Ross (DDG 71) fires a tomahawk land attack missile April 7. Petty Officer 3rd Class Robert Price / Navy

When a Reality-TV President Orders a Missile Strike

“Every new technology necessitates a new war.”

We are, by now, accustomed to televised wars.

For much of 2003, CNN was awash in the green, night-goggled view of bombs exploding over Baghdad. But it was the first Iraq war, in 1990, that offered viewers live broadcasts from the front lines—and buoyed cable news subscriptions as a result.

“They’re almost sheepish about the boost in business,” the Associated Press reported in 1991, “but cable television operators say interest in CNN’s round-the-clock coverage of the Persian Gulf war has paid off by attracting new subscribers.”

The U.S. strike on Syria ordered by President Donald Trump last week was, many critics say, a return to form for wartime television. The difference is this: Never before has America had a president known to be so interested in television programming.

“As it always does, the U.S. media last night was an almost equal mix of excitement and reverence as the bombs fell,” Glenn Greenwald wrote for The Intercept. “Where are all the grave predictions that he’s leading the world on a path of authoritarianism, fascism and blood and soil nationalism? They all gave way to War Fever.”

CNN’s Fareed Zakaria characterized the strike as a turning point for Trump—“I think Donald Trump became president of the United States last night,” he said—while Brian Williams, of MSNBC, seemed to find the attack awe-inspiring.

“We see these beautiful pictures at night from the decks of these two U.S. Navy vessels in the eastern Mediterranean,” Williams said during a broadcast. “I am tempted to quote the great Leonard Cohen, ‘I am guided by the beauty of our weapons.’ And they are beautiful pictures of fearsome armaments making, what is for them, a brief flight over to this airfield.”

“Guest after guest is gushing,” tweeted Sam Sacks, the co-founder of The District Sentinel, a website focused on federal policy. “From MSNBC to CNN, Trump is receiving his best night of press so far. And all he had to do was start a war.”

* * *

Vietnam is often called the first truly televised war. This isn’t exactly right. There were silent films depicting World War I, and government-made newsreels during World War II. But the Vietnam war was the first conflict for which there was a mass television audience in the United States. At the start of the Korean War, in 1950, just 9 percent of American households had a television. By the time the U.S. suffered its first casualties in Vietnam, less than a decade later, more than 85 percent of American households had TVs.

Vietnam was, in this way, the first “living-room war,” as it is sometimes called, a description that’s as apt as it is unsettling.

The media theorist Marshall McLuhan once argued that “every new technology necessitates a new war,” a viewpoint that his critics say unfairly absolves humans from blame. But history has shown us that any technology that’s used to document human life will eventually be used to document death, too.

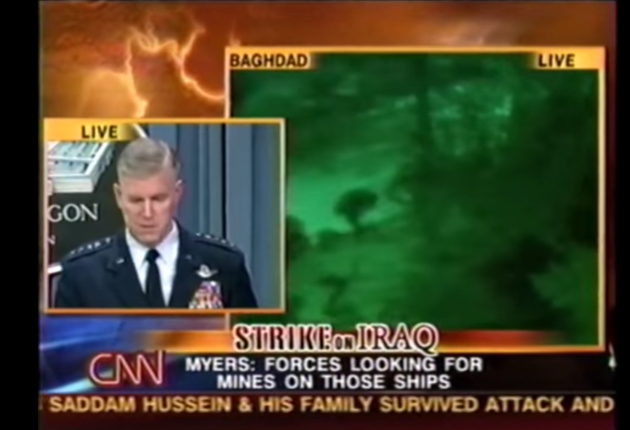

A screenshot of CNN’s coverage of the start of the Iraq War in 2003.

A screenshot of CNN’s coverage of the start of the Iraq War in 2003.

Real-time field reports of 21st-century wars, however, are “a long march from the work of Matthew Brady, the Civil War photographer whose pictures showed the dead, Americans all, stacked like cordwood,” David Carr, the late New York Timescolumnist wrote in 2003. “There, too, technology was destiny. Mr. Brady’s cumbersome photographic process put a premium on the stillness of the subjects, and no subjects are more patient than the dead. But as photography evolved toward lightweight cameras and higher-speed films, the dead became less visible.”

Brady was embedded with the Army of the Potomac, and he captured thousands of gruesome war scenes—he even toted a pop-up tent to use as a dark room so he could process photographs from battle. Today, his images of the Battle of Antietam are some of the most reproduced images of the Civil War. But when the public first saw them, in a gallery exhibition in 1862, Brady’s photographs depicted carnage unlike anything ordinary citizens had ever seen.

“As it is, the dead of the battlefield come up to us very rarely, even in dreams,” one reporter wrote in reaction to that exhibition at the time. “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

To see the dead of war was horrible, but also a technological marvel. The camera was still brand new at the time—so new that the very idea of light streaming through a lens and capturing a moment in time was novel enough to merit mention in the 1862 description of Brady’s work: “It seems somewhat singular that the same sun that looked down on the faces of the slain—blistering them, blotting out from the bodies all semblance to humanity, and hastening corruption—should have thus caught their features upon canvas, and given them perpetuity for ever. But so it is.”

A century later, as images from Vietnam were beamed onto rabbit-eared television sets in people’s living rooms, there was a question of what was being left out. “TV has not, despite all claims to the contrary, shown the real war,” The New York Times wrote in 1970. “Few films have shown men dying or being wounded, and, in fact, print journalism has been more explicit about the bloodshed.”

Paradoxically, television makes the hazards of war seem simultaneously more and less real. The viewer is left with the impression of unfettered access to the front lines of conflict, when what they’re actually seeing is a highly produced spectacle. (Often complete with special graphics and slogans, and dramatic music.) During the Vietnam war, *the majority of Americans could, for the first time, watch* the war unfold from the same comfortable spot on their sofas where they also watched Gunsmoke and The Ed Sullivan Show. Periodically, the war would be interrupted with a jingle for soap or cigarettes.

Also, when the war is on television, you can turn it off.

The real characters of American conflict were diminished by sharing an otherwise escapist medium, and they were quite literally diminished, too—“men three inches tall shooting at other men three inches tall,” as M.J. Arlen put it in The New Yorker in 1966.

Television has changed dramatically since then, not least of all because of the rise of internet news. Morning papers and nightly newscasts gave way to round-the-clock cable television and Twitter, yes, but even CNN coverage of wars is a different beast in 2017.

uring the Gulf War, cable TV was an endless string of reporters offering what little information they had from the Pentagon, and staticky phone calls with foreign correspondents on the ground. Today, along with military-provided imagery of missiles firing, there is an endless stream of guest analysts—panels of experts talking over one another, offering limited and often contradictory context.

“The problem is not that television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining,” wrote Neil Postman in his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. “Entertainment is the supra-ideology of all discourse on television. No matter what is depicted or from what point of view, the overarching presumption is that it is there for our amusement and pleasure.”

One of the strangest prospects about a possible Trump-led war is that the president, more than any of his predecessors (even Ronald Reagan, the movie star), has a preternatural instinct for television. If television producers treat news as “pure entertainment,” as Postman argued, Trump treats politics the same way.

Trump’s extraordinary instinct for television is matched by his appetite for it. He rarely sleeps, The Washington Post reported, and instead “watches enormous amounts of television all through the night.” During the presidential campaign, he told Chuck Todd, the Meet the Press host, that he got military advice by watching “the shows” on cable.

All of which suggests an even stranger cultural convergence than what we’ve seen in more than 50 years of war reporting being filtered through a medium biased toward entertaining people. We are now facing the prospect of a televised war, waged by a president whose worldview is formed not just by what he sees on television—but by the fundamental principles that drive television programming. The result is a feedback loop where television incentivizes war, while at the same time obscuring its grisly reality.

NEXT STORY: SOUTHCOM: ‘ISIS Is In the Western Hemisphere’