A month after President Trump took the oath of office, his chief strategist offered a controversial description of what Americans, including the 2 million career civil servants Trump now leads in the executive branch, could expect from the new president: Every day would be a battle for “deconstruction of the administrative state,” said Stephen Bannon, the man frequently described as the mastermind behind Trump’s nationalist agenda.

Bannon is no longer in the White House, but his remarks at a conservative political conference in February continue to reverberate through government.

Some interpreted Bannon’s comment as a reference to Trump’s classic Republican goals of reducing regulations, cutting taxes and shrinking government. But in a Manichean speech in Warsaw, Poland, in July, Trump warned of a danger “invisible to some but familiar to the Poles: the steady creep of government bureaucracy that drains the vitality and wealth of the people.”

As the Trump era has unfolded, the term “deep state” has come to mean something sinister to some on the far right. More than just signifying an impersonal, inept bureaucracy, it conjures a secretive illuminati of bureaucrats determined to sabotage the Trump agenda.

On the pro-Trump Mark Levin radio show, commentator Dan Bongino decried the ongoing investigation of Trump’s ties to the Russians during the 2016 campaign, saying, "They want a scalp, and believe me when I tell you the deep state is going to get one.”

Trump is being attacked, said a memo from a National Security Council staffer published in August by Foreign Policy, because he represents “an existential threat to cultural Marxist memes that dominate the prevailing cultural narrative.” Those threatened by Trump include “deep state actors, globalists, bankers, Islamists, and establishment Republicans.”

In July, Breitbart News—where Bannon presided before joining the Trump presidential campaign in August 2016, and to which he immediately returned after his departure from the White House a year later—publicized a report from the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee saying Trump faced seven times more leaks during the first 126 days of his administration than the previous two administrations.

“How many foreign allies are pulling back?” asked the Wall Street Journal’s Kimberley Strassel in a column titled “Washington’s Leak Mob.” “How many will work with a U.S. government that has disclosed so many military plans, weapons systems and cybersecurity tactics?”

President Trump takes reporters questions in the lobby of Trump Tower in New York on Aug. 15, 2017. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

A Hostile Takeover

Even before he took the oath of office, Trump took to Twitter to characterize suspected leakers in the intelligence community as behaving like Nazis. At the Justice Department, Attorney General Jeff Sessions in August issued a loud warning to would-be leakers, even as some career Justice staff continued spilling to the media their worries about Sessions’ policy reversals on such issues as immigration and affirmative action.

Also enlisting in the war against the deep state are right-leaning legal activists who use the Freedom of Information Act to target disgruntled career federal workers who use encrypted software to make anonymous political commentary unflattering to Trump.

But to many with years in government, the term “deep state” is disturbing. “Deep state is both inaccurate and grossly misleading,” said Nancy McEldowney, who retired in June as director of the Arlington, Va.-based Foreign Service Institute. “The term originated in the context of analyzing the situations in Turkey and Egypt, where I served, usually to talk about propaganda, dirty tricks, and even violence to overthrow the government,” she said.

“To refer to career civil servants in the U.S. government as some form of deep state is a clear attempt to delegitimize voices of disagreement," she added. “Even worse, it carries with it the potential for fear-baiting and rumor-mongering, and is really a dark conspiratorial term that does not correspond to reality.”

Chris Lu, President Obama’s deputy Labor secretary, rejects the notion that some entrenched deep state is undermining Trump’s political appointees. “The politicals set the direction of the agency, but they can only do it effectively if they tap into the expertise of the federal civil service,” he said.

Lu, now a senior fellow at the University of Virginia Miller Center of Public Affairs, says it’s important to remember why the civil service was created under the 1883 Pendleton Act. “Before then, there were stories of the amounts of time [President] Lincoln spent meeting with job seekers, with ads in Washington newspapers selling jobs under the spoils system and the tradition of incoming administrations kicking everyone out,” he said. Creation of the civil service was “one of the most important reforms of the past century and a half, and is one reason the federal government is still the most important and powerful organization in the world.”

But if the Trump team is misreading how government works, it is not the first new administration to do so. Every new president brings into office political appointees who are wary of “bureaucrats,” said Paul Light, Paulette Goddard Professor of Public Service at New York University. “Democrats historically have been as reluctant to work with careerists as Republicans, not because of the ideology but because of the desire for speed.”

To refer to career civil servants in the U.S. government as some form of deep state is a clear attempt to delegitimize voices of disagreement. Even worse, it carries with it the potential for fear-baiting and rumor-mongering, and is really a dark conspiratorial term that does not correspond to reality.

nancy mceldowney, former director of the foreign service institute

Democrats generally understand they will need federal employees to implement their policies, “though they may believe that those employees need to be liberated from rules,” Light added. “Republicans have the same hierarchy, but are motivated by a different goal. Both parties in the past have “come in saying, ‘We’ve got an agenda; we’ve got four years, maybe eight, so we can’t wait for action.’ ”

In the Trump administration, Light noted, many may agree with Bannon’s concept of a deep state, but are uncomfortable with that language.

Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon steps off Air Force One on April 9, 2017, at Andrews Air Force Base, Md. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Others are skeptical that many in Trump’s circles actually buy into the notion of a deep state. “If they had this theory of the deep state and were worried, the first thing they would do is appoint a lot of political appointees,” said Donald Devine, who headed the Office of Personnel Management in the Reagan administration.

Norm Ornstein, a longtime observer of Washington at the American Enterprise Institute, is appalled at what he sees as Bannon’s promotion of a “conspiracy theory of lawless people trying to undermine American values for their own warped sense and defying laws and property.”

In fact, Ornstein said, “we have career people and some political appointees who’ve been there some time who are essential to the functioning of government. They’ve been there through many administrations and have their own policy interests.” So yes, there is that web of people. “But my experience over many decades is that overwhelmingly they understand their role, and whether they like the policies or not, they follow the lead of administrations.”

In recent decades, there’s been “significant damage done,” Ornstein added, “in that when there’s a change in party, the newcomers tend to view many of those career people working for previous administrations as traitors you want to force out. The tensions are greater now in the era of polarized politics.”

Distrust Cuts Both Ways

Trump’s antipathy toward the career federal workforce may have been sealed on Inauguration Day, after a National Park Service employee retweeted Twitter messages comparing crowd sizes at the 2017 ceremony with those of the 2008 inauguration of President Obama. The effect, not favorable to Trump, prompted the new president to phone acting NPS Director Michael Reynolds to complain that his crowd size was underplayed. (A subsequent investigation by the Interior Department watchdog found no wrongdoing on the part of Park Service employees.)

One can see how this might have informed Trump’s impression of a deep state. Just six weeks later, Trump accused President Obama of “wiretapping” his conversations at Trump Tower in New York.

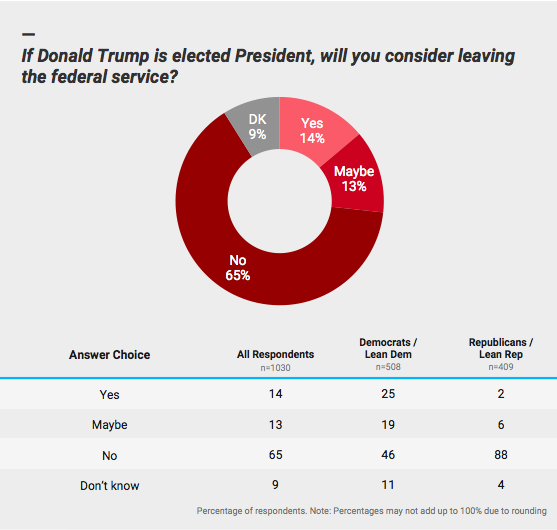

More than half of federal employees had said the previous October they would vote for Hillary Clinton, according to a Government Executive/Government Business Council survey. Just 34 percent were for Trump. (As many as a quarter of federal employees had said in an earlier Government Executive/GBC poll that they would resign were Trump to win the election.)

Campaign donations from federal employees for the 2016 cycle skewed toward Democrats, in some agencies by a factor of 10-to-1, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In recent months, the news media, which Trump often derides as “fake,” have published numerous essays and interviews with disgruntled federal employees, including one from a former State Department employee who accused Secretary Rex Tillerson of an “inherent distrust of the State Department and career officers.”

And when Sessions in August announced a reversal of Justice’s position on a case involving Ohio’s effort to purge rolls of inactive voters, career staff who had signed a related brief during the Obama years did not put their names on the Trump version.

Many of Trump’s staff and appointees had experience in previous Republican administrations, where, to varying degrees, political appointees came into agencies with an agenda to shrink the bureaucracy and make government less intrusive.

An Agenda With a Precedent

Indeed, President Reagan’s “government is the problem” theme had its heyday only three years after Democratic President Jimmy Carter had worked with Congress to enact the 1978 Civil Service Act, largely as an effort to professionalize government.

Devine, who ran personnel-related issues for Reagan’s transition team before becoming OPM director, recalls the scene in 1981 as one in which “unions were threatening job actions, and either sitting with their arms folded or not showing up.” Eventually, after federal air traffic controllers went on strike and Reagan fired them, “those job actions stopped.”

Most civil servants disliked Reagan. Devine, now a college professor, remembers an early speech on cutting bureaucracy he delivered to the American Society for Public Administration. It drew loud boos and multiple requests for printed copies. “My dealings with the bureaucracy showed me their first priorities were maintaining the status quo in their agencies, and they were certainly not Republicans,” he said.

The Reagan years, much like today, brought to Washington many appointees to run agencies charged with missions the appointees don’t endorse. One such example is Anne Gorsuch Burford, Reagan’s Environmental Protection Agency administrator. In 1981, with Reagan’s blessing, she began implementing a 22 percent budget cut and slashed regulations. After a scandal surrounding the $1.6 billion hazardous waste superfund cleanup program, she was cited for contempt of Congress. (Though Burford wouldn’t have mentioned a deep state, she did say later that Washington was "too small to be a state but too large to be an asylum for the mentally deranged.")

My dealings with the bureaucracy showed me their first priorities were maintaining the status quo in their agencies, and they were certainly not Republicans.

donald devine, former head of the office of personnel management

Career employees working under Burford recall the pressure she was under to please Reagan campaign donors such as the Colorado-based Joseph Coors beer family, and how Budget Director David Stockman would target programs for elimination without any debate. “I received a call from my boss’s deputy less than a month after the inauguration telling me my noise control program was being abolished, and the decision was not appealable,” recalled Chuck Elkins, who spent 25 years at EPA. “We regulated an industry for their noise, and one of the manufacturers had complained to Stockman.”

During the Reagan transition, Elkins attended a meeting where political appointees spoke frankly about favoring industry, he told Government Executive. He was deeply committed to the program’s mission, and the message from the new administration was disturbing. “My first reaction was ‘we can’t lose this,’ ” Elkins said. But soon his thoughts turned to the 100 people who would lose their jobs at a time when he himself had two kids in college. He responded by setting up a clinic on resume writing. Soon most employees found jobs with the Navy or the Interior Department, where Elkins did a stint before eventually returning to EPA to work in other areas.

Burford feared the bureaucracy enough to compile “an enemies list,” recalled Elkins’ colleague Ed Hanley. He recalled being summoned by EPA’s acting boss and handed “a yellow buck slip with seven names, all career,” with instructions that he should “get on top of these people, or something vague and threatening like that,” Hanley said.

It was left to Hanley to explain the limitations on firing career staff without cause. In the end, Burford signed off on some “questionable personnel actions to get her people in,” Hanley recalls, but ultimately Burford herself was fired and Reagan brought back the original EPA administrator William Ruckelshaus, whose tenure Hanley recalled as his “best years” at EPA.

One portion of the administrative state that shrunk under Reagan were the many agency support service workers, whose tasks were privatized, noted Don Kettl, professor of public policy at the University of Maryland. “All the cafeteria, sanitation, maintenance and other blue-collar workers were essentially wrung out of the bureaucracy because of Reagan,” he said. “It clearly put people on edge. The paradox is that there were more federal bureaucrats at the end of his administration because of his defense buildup.”

Reinventing the State

If there was a hidden cabal of resistant bureaucrats in the 1990s foiling the Clinton administration’s far-reaching Reinventing Government campaign, they had a funny way of showing it.

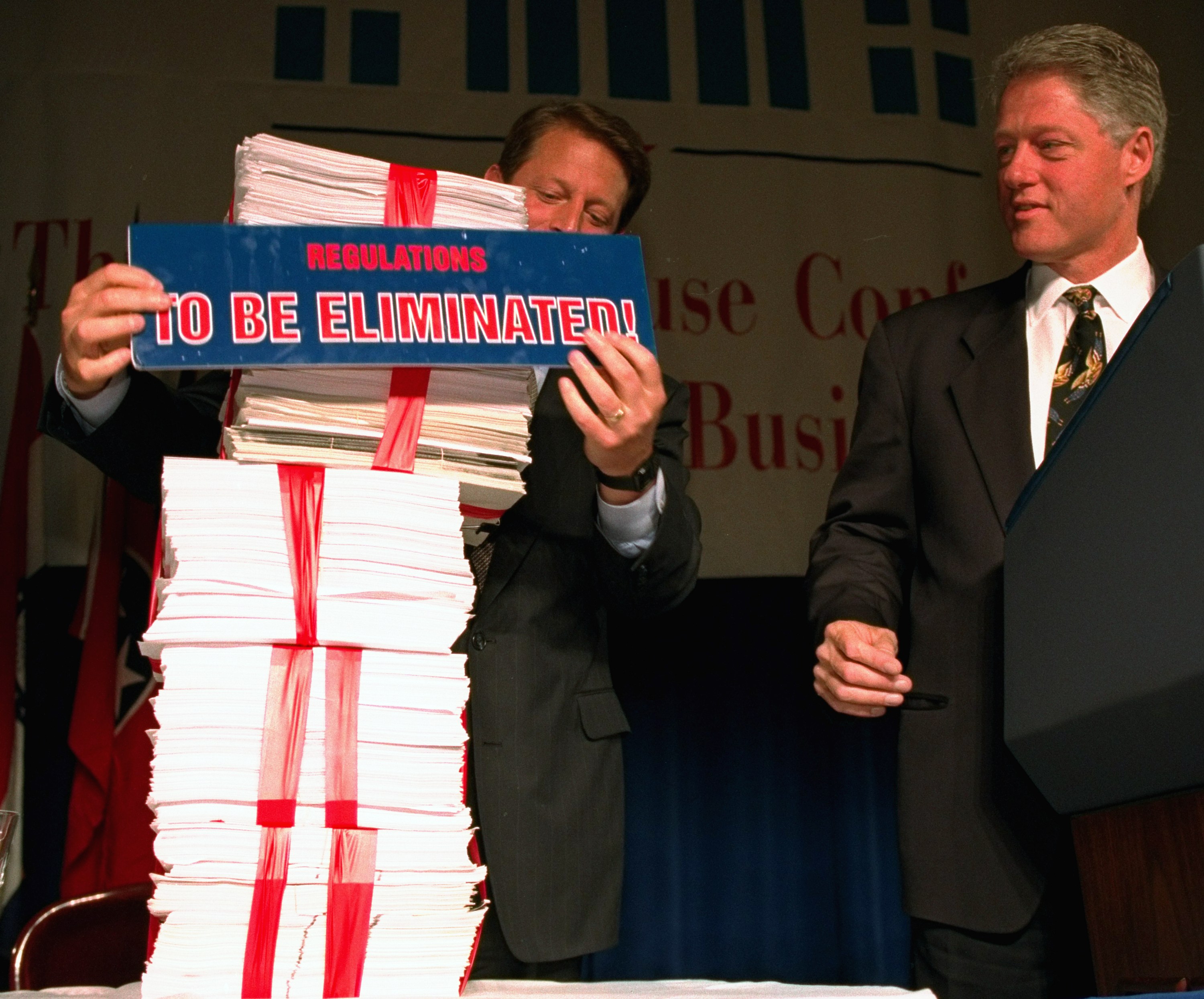

“A lot of the reform ideas came from the bureaucrats we recruited,” said Elaine Kamarck, the Brookings Institution scholar who directed the multi-year effort from the White House under Vice President Al Gore. “At one point in 1993, about 2,000 people were working on reinventing government tasks, several hundred of them detailed to the White House, with task forces in every agency,” she said.

The “weighty volume of recommendations” the effort produced came out of the career bureaucracy, added Kettl. “A large part of what was celebrated, such as the Hammer Awards for big-impact [reforms], came from leads generated by career officials, seized upon and promoted by Gore.”

President Clinton looks on as Vice President Gore displays a three-foot high stack of federal regulations to be eliminated on June 12, 1995. (AP Photo/Marcy Nighswander)

Some efforts met with resistance, recalled Paul Light. But many in the Clinton administration believed “hardworking feds needed to be liberated from rules.” New administrations in both parties often barrel in eager for action, Light said. The difference is that Democrats tend to understand that implementation requires federal employees, he said.

“Federal employees, to their credit, are committed to faithfully executing the laws” no matter what party holds the White House, Light added. “They don’t and shouldn’t change with each administration.”

Kamarck, author of Why Presidents Fail and How They Can Succeed Again, said, “Presidents get themselves in trouble by not understanding the bureaucracy.” In any organization of two million people, there is something going wrong and something going right at any given time. But even in times of crisis, the mail gets delivered, taxes are collected, Social Security checks go out and customs inspectors protect the borders.

Federal employees follow the law, not the president. If Trump walked into the Agriculture Department and proposed to abandon milk supports, the employees would “probably want selfies with him,” she said, but would then say, “Mr. President, thank you very much, but we can’t do that, it’s against the law.”

Trump’s Dilemma

Trump experienced a rare moment of bipartisan support in April, when he authorized the launch of 59 cruise missiles into Syria after its government used chemical weapons. He couldn’t have done it without an administrative state. “They can criticize the deep state all they want, but why 59 missiles, why that time of day, and why was it aimed at that particular spot in the desert?” asked Kettl. When Trump made a policy decision, “it was executed in a way that only people who knew what they were doing could do it.”

The Trump administration’s skepticism about the deep state has led to a number of self-inflicted crises and prompted endless discussion about the president’s decision-making process. The questions include why he issued a court-blocked travel ban last February without consulting Justice or the Homeland Security Department. Why he tweeted a promise to remove LGBTQ service members from the military without looping in the Pentagon. Why he threatened North Korea with “fire and fury” without a team of foreign policy specialists molding the language.

Ornstein bemoans what he sees as Trump’s “war on expertise, war on science,” as revealed in his “dismantling” of science advisory panels on the environment. He complains that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is “driving out some of the best and brightest career diplomats out of sheer incompetence, ignorance, indifference, and hostility.”

There’s a paradox, added Kettl, in complaining about a deep state and then taking such a long time to make political appointments. While the administration has an ambitious agenda, without appointees in place to implement its plans, it is reliant on career staff to get the work done.

The one area where Trump’s staff have demonstrated respect for career employees may be his management agenda with its proposed agency reorganizations to boost efficiency. Budget Director Mick Mulvaney, in tasking agencies to submit reform proposals, has stressed that his team is talking to the Government Accountability Office, the President’s Management Council, agency inspectors general as well as countless federal employees. “It is driven by career staff,” he told Government Executive. “There’s no way a political like me from the outside could do it.”

White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney fields questions from reporters during the daily press briefing at the White House on July 20, 2017. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Career employees “are the backbone of ensuring that programs are implemented, people are kept safe, and the government performs its role in providing economic opportunity,” said Chris Lu, the former deputy Labor secretary. “I probably spent much of my time with budget people and lawyers and information technology experts. The career employees understand a new administration wants to point the ship in a different direction, but they tell you how far you can turn it, how aggressively to move. Listening to them can make the difference in whether or not a policy change is successfully implemented or whether a regulation holds up in court.”

The label deep state “assumes there’s some kind of planned conspiracy going on,” said Devine, the Reagan-era veteran who still bemoans the obstacles to firing federal employees. “It is irrational to allow people to run around government doing anything they want, simply following the parochial interests of their agencies. Federal employees need and legally require political supervision, which was the essence of the Carter reforms, a lesson that the Trump administration Office of Management and Budget needs to explain to the White House rather than promoting a naïve version of the permanent bureaucracy.”

EPA alumnus Hanley addressed the deep state by recalling the time doomed EPA Administrator Burford showed up at a retirement party for longtime agency luminary Ed Turk. Having little to fear from the authorities on his last day, Turk told Burford, “Anne, I’ll leave you with this thought:

“When Democrats come to Washington, they arrive as an army of liberation. They turn to the civil service and say, `We love you, go forth and let 1,000 flowers bloom.’ Then comes the madness, and the Democrats wake up,” Turk said. “Then the Republicans arrive as a conquering army and put their heels on the neck of the civil service. But after about a year or 18 months, they realize that they actually need them to run the place. So they take their heels off the necks, and things are fine.”

Charles S. Clark joined Government Executive in the fall of 2009. He has been on staff at The Washington Post, Congressional Quarterly, National Journal, Time-Life Books, Tax Analysts, the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, and the National Center on Education and the Economy. He has written or edited online news, daily news stories, long features, wire copy, magazines, books and organizational media strategies.